Even if you haven’t heard of B. Kumaravadivelu’s work on “postmethod” pedagogy, you probably have experienced its effects: the last trendy methods of language pedagogy—Communicative Language Teaching (CLT), Task-Based Language Teaching (TBLT), and Content Language Integrated Learning (CLIL)—are at least 20 years old. At some point, around the year 2000, the carousel of “trendy” language teaching methods coming from the Global North (particularly the U.S.) stopped turning. Now, instead, people are primarily interested in contexts of language teaching (needs analysis, language learning for specific purposes, sociocultural approaches to studying learner motivation, etc.). Personally, I think one reason is the impact of Kumaravadivelu’s writings about “postmethod.” In this blog post, I summarize his key article on the subject, Kumaravadivelu (2001) in TESOL Quarterly. I honestly believe that no one should practice language teaching without reading it!

Kumaravadivelu, B. (2001). Toward a postmethod pedagogy. TESOL Quarterly, 35(4), 537-560. https://doi.org/10.2307/3588427

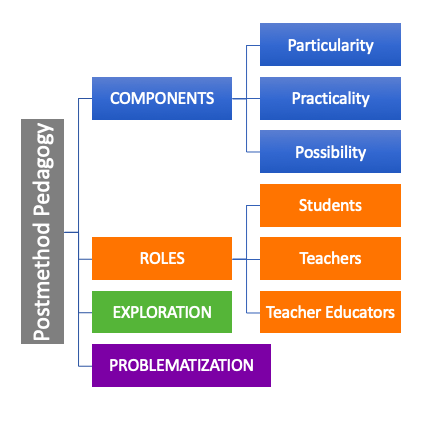

“Pedagogy” does not only mean teaching strategies, instructional materials, curriculum objectives, or tests/assessments. It also refers to a wide range of historical, political, and sociocultural experiences and ideologies that directly or indirectly influence education, including language education. For a language pedagogy to succeed given a specific teacher and group of learners, in a specific school and location, and for specific purposes, we need to observe what Kumaravadivelu calls the 3 P’s of “postmethod” pedagogy—PARTICULARITY, PRACTICALITY, and POSSIBILITY.

Particularity

In this first section on Particularity, Kumaravadivelu outlines some of the negative effects in different parts of the world of “trendy” language teaching methods coming from the Global North, “developed countries” (mainly the U.S. and U.K., and mainly to do with English teaching). And yet, “All pedagogy, like all politics, is local. To ignore local exigencies is to ignore lived experiences.” (p. 539). Take the widespread promotion of Communicative Language Teaching (CLT) to teach English. Are all learners’ goals to chit-chat fluently in English on fun topics like sports, holidays, movies, etc.? This is a common use of English in the U.S. and U.K., and of the upper-middle-class in many parts of the world, but for the vast majority of people in non-English-dominant countries, people need English for different purposes: grammar tests to get into university, receptive reading ability of equipment manuals, etc. Many people find trying to chit-chat in English absurd (as if you are making a joke), or worse, condescending to their fellow farmers, fishers, or factory workers.

Chick (1996) called CLT “naive ethnocentrism,” while Shamim (1996, p. 109) found that promoting it where it was not appropriate could make the teacher “terribly exhausted” and the learners put up “psychological barriers to learning.” Canagarajah (1999) found that a CLT English course in Sri Lanka drove university students to take outside private tutoring on grammar so they could actually learn something useful to them—to pass English exams to graduate—while writing graffiti all over the course textbook, which was a hand-me-down from the West involving “fun” (note the sarcasm) topics like whether to consider buying things they would never be able to afford in their lives. (All of these studies are cited in this article by Kumaravadivelu, 2001, pp. 539, 543).

Particularity means that the generic knowledge you learn in a teacher education program can only help you so much. This puts the responsibility on you, the pre-service or early career teacher, to listen and learn from your internship experiences. What are learners’ present and future needs? How do we know that these are being met through curriculum design, instruction, and assessment? You can learn from more and less experienced colleagues, from students, and from researching the context on your own. This does not mean believing everything you read or hear, but trying to learn as much as you can. Which brings us to the next point: Practicality.

Practicality

It is important to know that Kumaravadivelu’s definition of practicality is not “concrete steps of what to do,” as in a cookbook. It is more like: “education practitioners’ freedom and autonomy to act upon their knowledge, observations, and intuitions.” In other words, practicality means that teachers, teacher educators, and students should not be seen merely as implementers of academic theories (Giroux, 1988; Kincheloe, 1993). Teachers need the tools for exploration that allow them to theorize based on their practice. Sometimes a teacher knows what to do based on empirical evidence they have collected; other times, it is just a “gut feeling” based on enough experience that tells them what to do. In any case, teachers who are both experienced and reflective have a

powerful sense of what works and what doesn’t; of which changes will go and which will not—not in the abstract, or even as a general rule, but for this teacher in this context. In the simple yet deeply influential sense of practicality among teachers is the distillation of complex and potent combinations of purpose, person, politics, and workplace constraints. (Hargreaves, 1994, as cited in Kumaravadivelu, p. 542; my bold)

Kumaravadivelu further states: “Teachers’ sense making matures over time as they learn to cope with competing pulls and pressures representing the content and character of professional preparation, personal beliefs, institutional constraints, learner expectations, assessment instruments, and other factors” (p. 542; my bold). [Not all these pulls and pressures are equally valid, but the best thing to do comes from the distillation of them into informed action, not the bowing to a single one. I have also blogged about that point here, in my summary of Jaspers’ (2019) essay about the need for more equitable partnerships between translanguaging scholars and language educators.]

Empowering teachers is necessary for empowering students. Teachers must understand and transform the possibilities inside and outside the classroom as active agents, in order to lead students to do the same. This brings us to the third P, which is Possibility.

Possibility

Teachers’ and learners’ pedagogical actions (“what” they do to teach/learn), and their perceptions about the bigger purpose of doing so (“why” we do it this way) are influenced by (1) their identities developed over time, (2) their interpersonal interactions with others in the classroom at that very moment, and (3) the broader social, economic, and political environments in which they have grown up.

I will give an example here not from Kumaravadivelu’s article, but from Henderson and Sayer (2020). They examined U.S. elementary school teachers’ belief systems about language use in the classroom. Two participants were a Latina teacher and a white male teacher, both fluent in Spanish. They found that both embraced bi/multilingual pedagogy, both taught in an engaging way, both cared for students, and both were engaged with social justice issues. However, the Latina teacher was stricter about “proper” English and Spanish use. The reason was that she was more likely to “pay” for improper use of language with people seeing her in terms of deficit or lack, whereas the white male teacher’s relaxed use of language would not reflect negatively on his professionalism. Yet the Latina teacher was not an uncritical educator. On one occasion, she directly confronted the idea that fairer skin was more beautiful by saying to the Latinx children, “People sunbathe so that they can have skin like us,” after one student made a negative comment about brown skin. Was either teacher wrong in his/her teaching approaches? Not really—but the approaches reflected the individual in terms of factors (1), (2), and (3) above.

This individual identity often plays out through language: “language is the place where actual and possible forms of social organization and their likely social and political consequences are defined and contested. Yet it is also the place where our sense of ourselves, our subjectivity, is constructed” (Weedon, 1987, as cited in Kumaravadivelu, 2001, pp. 543-544; my bold). Here’s another illustrative example, this time involving students: the same classroom environment, the very same social and language practices, can affect different students in different ways due to their identity positioning. In an English class, is a student a more “standard” speaker of English with less multilingual knowledge, or a less “standard” speaker of English with more multilingual knowledge (Rajendram, 2021)? In a dual language program, are they a native speaker of the majority language outside the classroom, or the other language that students are trying to learn in the program (Hamman, 2018)? In an immigration context, is the student a newcomer academically fluent in the home country’s dominant language (e.g., one who is using that knowledge to acquire academic English by leaps and bounds), or a less academically proficient student fluent in English who speaks the home country’s language as a heritage language (Mendoza, 2020)? Even more simply, are classroom participants in the class linguistic majority or minority (Allard, Apt, & Sacks 2019)?

For Kumaravadivelu, in a pedagogy of possibility, the forms of social organization and the sense of selves that we take for granted are changed in an intentional and perceivable way. The classroom linguistic majority does not dominate discussion. The language that is minoritized in the wider society is prioritized by teachers and students. The less multilingual students who speak English as L1 feel their limitations in that respect, and admire those who are more multilingual. First and heritage language speakers of the home country’s language form connections instead of separate communities of practice. As Kumaravadivelu powerfully puts it,

language teachers can ill afford to ignore the sociocultural reality that influences identity formation in the classroom, nor can they afford to separate the linguistic needs of learners from their social needs. In other words, language teachers cannot hope to fully satisfy their pedagogic obligations without at the same time satisfying their social obligations. (p. 544; my bold)

In a pedagogy of possibility, you start to see yourself—and other classroom participants—in different ways because of the critical social restructuring, which, though collaborative, is often led by the teacher.

Actualizing the Pedagogy

In this section, Kumaravadivelu talks about the roles that students, teachers, and teacher educators must play to combine the 3 P’s, which are interconnected, but whose effect is greater than the sum of the parts.

Postmethod learners are autonomous learners. Their autonomy takes multiple forms—academic, social, and liberatory. Academic autonomy is individual. The learner needs to identify and use their preferred learning strategies and styles, but also stretch themselves and build on the gaps (e.g., if they’re used to more communicative language learning, they should try out more analytic/grammar-based learning, and vice versa). They need to monitor their own progress and find opportunities to learn beyond the classroom. Social autonomy is collaborative. The learner must (i) actively seek the teacher’s input and feedback, (ii) be willing to cooperate with members of their learning community (classmates) by forming small groups, dividing responsibilities, and reporting back to the group, and (iii) take advantage of social and cultural events to communicate with competent—not necessarily native!—speakers of the language. They must also develop sensitivity and empathy to learners not like them, e.g., those with different learning styles and proficiencies. Finally, liberatory autonomy means that the learner can “recognize sociopolitical impediments to realization of their full human potential” and work to acquire “tools necessary to overcome those impediments” (p. 547). For example, learners can investigate how rules for language use are socially constructed and whose interests those rules serve.

An important condition for students to find their identities as autonomous learners is for teachers to also be autonomous. Postmethod teachers need confidence and competence to build and implement their theory of practice. A certain amount of teaching experience is required, but this alone is not enough, because reflection is also important [see a book by Amy Tsui for a detailed empirical investigation of this point about experience + reflection]. Postmethod teachers’ theories of practice are “responsive to the particularities of their educational contexts and receptive to the possibilities of their sociopolitical conditions” (Kumaravadivelu, 2001, p. 548). Such teachers have to have enough autonomy in pedagogical decision-making, as well as knowledge gained from both formal and informal educational experiences. They will then come to know “what to do” by thinking through a gazillion factors, both consciously and subconsciously, according to their schema of experience, which continually “evolves over time, through determined effort” (p. 549). And just as students have to go beyond academic and social autonomy to liberatory autonomy, teachers must also think about pedagogies of Possibility, not just those of Particularity and Practicality: “Otherwise, teacher self-development will remain sociopolitically naive” (p. 549). Kumaravadivelu cites Hargreaves (1994, p. 74), who states that such naiveté occurs

when teachers are encouraged to reflect on their personal biographies without also connecting them to broader histories of which they are a part; or when they are asked to reflect on their personal images of teaching and learning without also theorizing the conditions which gave rise to those images and the consequences which follow from them.

In other words, teachers need to ask themselves why they “had” to study abroad in an Inner-Circle English-speaking country, or why they are such a fan of this or that method. In addition, teachers must keep “eyes, ears and mind open in the classroom to see what works and what does not, with what group(s) of learners, and for what reason, and assessing what changes are necessary to make instruction achieve its desired goals” (p. 550). The research tools for this purpose are not complicated. Thoughtfully designed questionnaires and interviews—which colleagues can give feedback on—can tell teachers a lot about their students’ “learning strategies and styles, personal identities and investments, psychological attitudes and anxieties, and sociopolitical concerns and conflicts” (p. 550). Research questions to investigate using these methods should be those that interest learners, teachers, or both, and can cover classroom management, teaching and learning, or wider social issues. One often-fruitful topic is “the potential mismatch between teacher intention and learner interpretation” (p. 551) when any act regarding classroom management, teaching and learning, or social issues is committed by the teacher.

In this research that teachers do, by themselves, with peers, or with students, the resources participants bring to knowledge construction (e.g., sociocultural, linguistic) are very valuable. In such inquiry, teachers can also dialogue with colleagues at their school or more distant peers/scholars through online correspondence. The point is for the teacher to question—and thereby lead students to question—assumptions about language(s) and language learning, so they can reflect on what further actions to take as a result. Such activities do not need to be “on the side” of day-to-day instruction, but can be built into the very core of the class, integrated with the course structure and learning outcomes.

Finally, postmethod teacher educators should not see themselves as modelling “good” teacher behaviours and evaluating pre-service teachers’ mastery of these behaviours. This transmission model cannot create self-determining postmethod teachers. As Kumaravadivelu points out, teacher educators, who are teachers themselves, should get to know teachers (their students) in terms of what they bring with them to the classroom. What are their notions of good and bad teaching? How are these based on their prior experiences? How can they learn to question their assumptions, while also cultivating their personal strengths, voices and visions? The answer is through a dialogue with the teacher educator, what Bakhtin (1981) calls responsive understanding (as cited in Kumaravadivelu, 2020, p. 552). Kumaravadivelu explains:

the primary responsibility of the teacher educator is not to provide the teacher with a borrowed voice, however enlightened it may be, but to provide opportunities for the dialogic construction of meaning out of which an identity or voice may emerge. (p. 552).

This requires dialogue between at least two people—e.g., the teacher and teacher educator, or a group of teacher candidates. People must be allowed to be proud of, and draw on, their individual linguistic, cultural, and pedagogic capital, and their values, beliefs, and knowledge, while respecting that of others; “then the entire process of teacher education becomes reflective and rewarding” (p. 552). Teacher educators can also show teachers how to track their beliefs, assumptions, and knowledge as these evolve over time, throughout their teacher education program and beyond [e.g., through journals, forums, vlogs… public or private]. All of this involves Bakhtinian dialogue—with theories, with others, with the self; involving both complementary and contrasting voices (including conflicting voices within oneself). Kumaravadivelu believes that discourse analysis, of societal discourses and classroom talk, and of webs of overlapping and contrasting discourses, is a key skill that teachers need to learn (p. 553). Teachers should also read critical authors who have raised the TESOL profession’s consciousness about the power and politics, ideologies, and inequalities that inform second language education. [A lot of good research on this was done in the 1990s and early 2000s by people like Phillipson, Tollefson, Benesch, Canagarajah, and Norton.]

One powerful teacher education strategy is “connecting the generic professional knowledge base available in the professional literature directly and explicitly to the particularities of learning/teaching contexts that prospective teachers are familiar with or with the ones in which they plan to work after graduation, thereby pointing out both the strengths and the weaknesses of the professional knowledge base” (p. 553). A model for this that I know is the Double-Layered Community of Practice (Lee & Brett, 2015), developed at the University of Toronto. In this case, a teacher education course was extended to encompass before, during, and after practicum. It was designed so that teachers would collect data from their practicum schools and use this data as material for the teacher education course (i.e., materials that they and their classmates had to study). This made them do investigations of Particularity, enabled their teacher autonomy as Practicality, and required dialogue with experienced co-teachers at their schools AND classmates/professors at the university to explore Possibility.

As Kumaravadivelu notes, such inquiry “transforms an information-oriented system into an inquiry-oriented one” (p. 553).

Conclusion: Exploration and Problematization

The concluding sections of Kumaravadivelu’s paper have to do with the benefits and challenges of postmethod pedagogy. Clearly, postmethod language pedagogy offers a lot of individual and collaborative empowerment to engage in knowledge construction—centering students, teachers, and teacher educators rather than scholars, academics, and researchers. Local knowledge is prioritized over generalizable knowledge, even though there is “no reason in principle why individual understandings should be incapable of being brought together towards some sort of overall synthesis” (Allwright, 1993, as cited in Kumaravadivelu, 2001, p. 554). Formal teacher education programs should develop teachers who can engage in such inquiry, using the tools for studying learning strategies and styles, personal identities and investments, psychological attitudes and anxieties, and sociopolitical concerns and conflicts, and engaging in discourse analysis of classroom interactions and wider societal ideologies.

The challenge (it’s not really a problem) is that pointed out by Kennedy (1999, as cited in Kumaravadivelu, 2001, p. 555): when teachers engage in this kind of powerful inquiry, they don’t just change their teaching methods, but their attitudes, beliefs, and identities—about “good” teaching, about students, about their teaching contexts, about their own teaching styles and abilities. They also get into some very sticky situations. For example, they may become aware of many competing interests (personal beliefs, institutional constraints, students needs and wants, and if students are minors, parental needs and wants, standardized tests, and admissions criteria of postsecondary institutions). They may confront the social, economic, and political contexts in which they work, which in some places leads to jail.

As for the other stakeholders, students may realize they do not all want the same thing—and have to grapple with their selfishness as individuals and groups “to maximize, monitor, and manage their autonomy for the individual as well as the collective good” (p. 556). For teachers to be empowered, administrators and institutions also have to adapt, give of themselves, question their beliefs and biases, and engage in the same inquiry processes. Ultimately, postmethod pedagogy requires everyone to be their best selves; the question becomes: “in what ways can these participants collaborate, and how can their differential and possibly conflicting goals be reconciled for the benefit of all?” (p. 556). Because there are no simple answers, postmethod pedagogy is always a work in progress.

Despite these challenges, Kumaravadivelu believes it is the right way to go. Previously, the organizing principle for language learning and teaching was method. Prior “revolutions” (i.e., CLT, TBLT, CLIL) never went beyond the idea of a new pedagogical method. In the second half of the 20th century, methods revolutions “guided the form and function of every conceivable component of L2 pedagogy, including curriculum design, syllabus specifications, materials preparation, instructional strategies, and testing techniques” (Kumaravadivelu, 2001, p. 557). However, the 3 P’s are an alternative organizing principle connecting learners, teachers, and teacher educators—promising “a relationship that is symbiotic and a result that is synergistic” and opening up “unlimited opportunities for the emergence of postmethod pedagogies that can truly serve the interests of those they are supposed to serve” (p. 557).

References

Allard, E. C., Apt, S., & Sacks, I. (2019). Language policy and practice in almost-bilingual classrooms. International Multilingual Research Journal, 13(2), 73-87. https://doi.org/10.1080/19313152.2018.1563425

Allwright, R. L. (1993). Integrating “research” and “pedagogy”: Appropriate criteria and practical problems. In J. Edge & K. Richard (Eds.), Teachers develop teachers research (pp. 125-135). London, UK: Heinemann.

Bakhtin, M. M. (1981). The dialogic imagination (trans. C. Emerson & M. Holquist). Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Canagarajah, A. S. (1999). Resisting linguistic imperialism in English teaching. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Chick, K. (1996). Safe-talk: Collusion in apartheid education. In H. Coleman (Ed.), Society and the language classroom (pp. 21-39). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Giroux, H. A. (1988). Schooling and the struggle for public life: Critical pedagogy in the modern age. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Hamman, L. (2018). Translanguaging and positioning in two-way dual language classrooms: A case for criticality. Language and Education, 32(1), 21-42. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2017.1384006

Hargreaves, A. (1994). Changing teachers, changing times. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Henderson, K., & Sayer, P. (2020). Translanguaging in the classroom: Implications for effective pedagogy for bilingual youth in Texas. In J. MacSwan & C. Faltis (Eds.), Codeswitching in the classroom: Critical perspectives on teaching, learning, policy, and ideology (pp. 207-224). New York, NY: Routledge.

Kennedy, C. (1999). Introduction—learning to change. In C. Kennedy, P. Doyle, & P. Doyle, C. Goh (Eds.), Exploring change in English language teaching (pp. iv-viii). Oxford, UK: Macmillan Heinemann.

Kincheloe, J. L. (1993). Toward a critical politics of teacher thinking: Mapping the postmodern. Westport, CT: Bergin & Garvey.

Lee, K., & Brett, C. (2015). An online course design for inservice teacher professional development in a Digital Age: The effectiveness of the Double-layered CoP model. In M. L. Niess & H. Gillow-Wiles (Eds.), Handbook of research on teacher education in the digital age (pp. 55-80). IGI Global.

Mendoza, A. (2020). What does translanguaging-for-equity really involve? An interactional analysis of a 9th grade English class. Applied Linguistics Review, pp. 1-21. Early view. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2019-0106

Rajendram, S. (2021). Translanguaging as an agentive pedagogy for multilingual learners: affordances and constraints. International Journal of Multilingualism, 1-28. Early view. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2021.1898619

Shamim, F. (1996). Learner resistance to innovation in classroom methodology. In H. Coleman (Ed.), Society and the language classroom (pp. 105-121). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Weedon, C. (1987). Feminist practice and poststructuralist theory. London, UK: Blackwell.

2 thoughts on “What is “postmethod” language teaching and why has it been so influential?”

Comments are closed.