This is a summary of a study that investigated the affordances and constraints in translanguaging-to-learn in an officially English-Medium 5th grade classroom in Malaysia where students were trilingual in Tamil, Malay, and English (Rajendram, 2021). I believe this study is valuable for anyone who studies translanguaging, in any educational context, for two reasons. First, data collection was extensive and data analysis thorough; therefore, the claims are strongly supported by the evidence. Second, the data address the important question of how students can use their whole language repertoire to learn and navigate the social life of the class (i.e., to translanguage), but at the same time, in the same dialogues, show domains of language acquisition/use and distinct languages in identity positioning.

Rajendram, S. (2021). Translanguaging as an agentive pedagogy for multilingual learners: Affordances and constraints. International Journal of Multilingualism. Early view. 1-28. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2021.1898619

This study investigated translanguaging’s affordances and constraints in an officially English-Medium 5th grade classroom. The classroom was in a school that served a white-collar Tamil community in Malaysia. Teacher and students were trilingual in Tamil, Malay, and English. The teacher routinely reminded students about an English-only policy, but it was unnatural for her and them to follow it all the time: thus, (i) when, how, and why people translanguaged was the subject of the investigation, as well as (ii) the ideological constraints to drawing on other languages apart from English to learn, as shown by the teacher’s and students’ shaping of the classroom language policy or medium of communication in group work.

Rajendram begins with a common overview of how “translanguaging posits that multilingual speakers draw on the features of their diverse language repertoires in a dynamic, flexible and functionally integrated way to convey and construct meaning, make sense of their experiences, and gain understanding and knowledge” (pp. 1-2), citing the work of Suresh Canagarajah, Angel Lin, Ofelia García, Ricardo Otheguy, Li Wei, and Zhu Hua. Learners translanguage with minimal pedagogical effort from teachers, even in classrooms with English-only policies (Canagarajah, 2011). This is because other language resources in the repertoire are affordances for learning. Van Lier (2008) defined affordances as resources available in the learning environment that are “mediated by social, interactional, cultural, institutional and other contextual factors” (p. 171). What is unusual about Rajendram’s study is that it tries to get into the minds of child learners (late elementary) to see translanguaging affordances from their point of view “while also examining how their discursive practices are shaped and at times constrained by factors both within and beyond their classroom” (Rajendram, 2021, p. 4).

Context of the Research

The study took place in the state of Selangor in the west of Malaysia, a country where 137 languages are spoken (World Atlas, 2018). As Rajendram explains (p. 4), about two thirds (68.6%) of Malays are from the Bumiputera group, which comprises people who are indigenous or at any rate whose ancestors arrived in Malaysia during ancient times, while Malaysian Chinese make up 23.4% of the population, and Malaysian Indians 7.0% (Malaysia Department of Information, 2017). The remaining 1% are non-Malay residents and foreign workers from countries such as Indonesia, Philippines, Bangladesh, Thailand, and Cambodia.

The school, Bukit Mawar (Rose Hill) was officially Tamil-medium, with English taught four times a week from grade 1 onwards. The participants were 31 students (19 girls and 12 boys, aged 10-11) in a gr. 5 classroom. Most came from upper-middle class families and had parents who were engineers, lecturers, lawyers, business executives, and bank managers. It is unlikely that their English input came from school only, and they had an upper-intermediate level of English proficiency. In addition, they could also converse in the national language, Malay (even though they knew their Malay was not seen as standard or native-like).

The teacher, Ms. Shalini, had taught at Bukit Mawar for 26 years. Like her students, she was a Malaysian-born Indian who spoke Tamil, Malay, and English. She enforced an English-only policy, and if she heard any Tamil or Malay, she would call out, “English only!” This may not be as face-threatening as it first appears. Given that Tamil, not Malay, was the language that most often “encroached” on English, and these children’s other academic subjects at school were taught in Tamil, and their parents did important business in Tamil, Ms. Shalini’s recurring reminder might have meant little more than “Let’s follow the classroom policy to maximize our exposure to English” (no face threats), especially since she, like the students, was also a middle-class, L1 Tamil, Indian-Malay who wanted to work on monolingual as well as plurilingual acquisition. At the same time, leaners “were situated within a sociocultural context where proficiency in the dominant languages of English and Malay was seen as a marker of overall language ability” (p. 7). This wider context is connected to two key findings: (1) when students told each other, “English only!” it led to undermining of individual and family funds of knowledge, as not every student had quite the same access to English and proficiency in that language; (2) the class as a whole often deprecated their Malay proficiency, and their use of Malay to translanguage was limited.

Ms. Shalini and Rajendram were already close colleagues for five years before the study, so the former welcomed the latter into the classroom to observe the students for 6 months for PhD research. Rajendram states: “As I used a naturalistic case study design, the teacher and students were not told to do anything differently” (p. 5). It was normal for Ms. Shalini to remind students to speak English from time to time, just as it was normal for her to let them translanguage in small group interactions, as if she didn’t notice—an arrangement that is probably very common in K-12 EFL classrooms. It is socially and pragmatically sensible, and has face validity for both students and teachers, but doesn’t harness the affordances of pedagogical translangauging in materials creation (Allard, Apt, & Sacks, 2019), vocabulary teaching (Leonet, Cenoz & Gorter, 2020), English for Academic Purposes (Lin, 2016) and building a supportive multilingual learning community (Woodley & Brown, 2016).

Methods

English class met four times a week: twice for an hour and twice for half an hour. (This totalled 3 hours of instruction per week, and if students had not been not-middle class, this amount of exposure at school would not have been enough to help them reach their upper-intermediate conversational proficiency.) The lessons followed a standard curriculum for primary school English, which had units such as “Malaysian Folk Tales, Money Matters, Tales from Other Lands, Safety Issues, The Digital Age, Friends from Around the World, and Pollution,” (p. 5), with each unit lasting about two weeks. In many lessons, there were activities in groups of three to five. Students wrote and performed poetry; wrote stories, reports, and essays; read and answered comprehension questions; made posters; rehearsed and presented dramas; created and solved puzzles; studied maps; discussed current events; and read/recreated graphic novels with a teacher who was fluent in English and their other language(s). Just this list of activities is indicative of the rich intertextual literacy practices of a middle-class EFL curriculum. Note that this was “only” an EFL class, focused on language rather than content—in contrast, English Medium Instruction (EMI) classes in Asia and Africa (in which academic subjects are taught in English to students from less privileged backgrounds) often sadly looks like this. On the other hand, what these students presently enjoyed was not for the long-term. Tamil-medium schools are allowed to function at the elementary level, but not the secondary or tertiary level, because of the hegemony of Malay in Malaysia—a form of linguistic discrimination that would put them at a disadvantage in their later educational years.

For data collection, Rajendram placed a mini camcorder and two voice recorders on each group’s table (usually one device is common!) and transcribed the multilingual data using Tamil script and the Latin alphabet for English and Malay. She also interviewed all 31 learners in the class, in their language(s) of choice, to elicit “their feelings and perceptions towards their teacher’s classroom language policy, their feelings about the languages they spoke, their language choices in and outside the classroom, and the reasons for their language choices across these different contexts” (p. 6).

For data analysis, she used Sociocultural Critical Discourse Analysis (Rajendram, 2019), a method that she developed by combining Sociocultural Discourse Analysis (Mercer, 2004) and Critical Discourse Analysis (Fairclough, 1995) to analyze students’ interaction (pp. 6-7) in terms of both construction of knowledge and individual identity positioning. She coded 4,389 speech acts across 50 transcripts inductively to describe the “translanguaging constellation” of each act—English, Malay, Tamil, English/Malay, Malay/Tamil, Tamil/English, and Tamil/English/Malay—and the specific function it served in the context of the collaborative activity. And this was just the first stage! The second stage “focused on interpreting the purposes and affordances of translanguaging, and explaining the factors influencing learners’ use of translanguaging” (p. 7). To do this, she drew on interview data. She paid close attention to responses that indicated personal discourses related to translanguaging, as well as broader language ideologies from teachers, parents, community, and society (p. 8).

Findings

Two thirds, or 66% of the 4,389 speech acts, showed translanguaging: English/Tamil, English/Malay, Malay/Tamil, or all three languages. Rajendram describes that learners engaged in translanguaging that was both pedagogical and spontaneous, and did so “strategically and intentionally in order to scaffold one another’s language learning and fulfil linguistic-discursive functions” (p. 8). They felt very comfortable translanguaging in small group interaction, e.g., “Thiva explained that she usually used Tamil to ask her group members about words she did not know”; “many learners explained that they translanguaged to help their friends who were having difficulties understanding words, phrases, or sentences in English” (p. 10), etc. Their translanguaging was mutually supportive—as Elango said: “If I don’t understand anything in English, I’ll ask Pravin. Other times, Pravin will ask me” (p. 10), and this pair was not exceptional.

Likely because (i) the school allowed them to develop academic proficiency in their L1, Tamil, (ii) they were all from the same ethnolinguistic and middle-class background, and (iii) all were conversationally proficient in English, but not to the same degree, “translanguaging was not just a temporary bridge to English proficiency for them; neither was it a rigid structure to be removed when no longer needed” (p. 11). Their languages were always interdependent, and learners described translanguaging with words like happy, enjoyable, and comfortable. Moreover, Rajendram noted that translanguaging in group work was not led by any one individual, as students took turns leading the group: “translanguaging was essential for creating positive interdependence, equal participation, and individual accountability, all components of successful collaborative learning” (p. 12).

On the other hand, language use was also domain-specific and sometimes entirely normative. For example, when students translanguaged across Tamil and English during assigned tasks, it was often to use Tamil to negotiate how to say something “correctly” or “appropriately” in the English product. This is what Rajendram (2019) called the linguistic-discursive function:

The good thing, however, was that students used the words to talk about academic concepts in their home language and not just in English, thanks to their academically-oriented elementary education in Tamil, unlike these elementary students in a dual language class studied by Hamman (2018), who were taught reading, writing, and math in Spanish but content-rich science and history in English. This is what Rajendram (2019) called the cognitive-conceptual function:

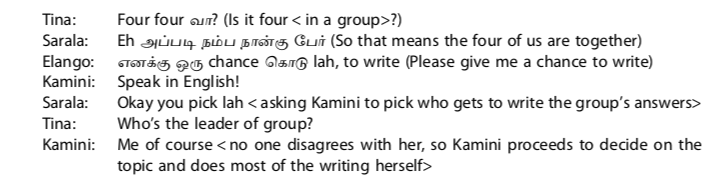

Translanguaging (mostly English-Tamil and to a far lesser extent English-Malay, Tamil-Malay, or English-Malay-Tamil) was also used to socialize, express identity, and access cultural knowledge. On the other hand, there were constraints to translanguaging. Students “did not use all the named languages in their repertoire (Tamil, English, Malay) equally, although they had similar levels of proficiency in all three languages. In addition, there were certain small groups in which translanguaging was used less frequently overall” (p. 16). The unfortunate finding was that these groups were dominated by students with more advanced English proficiency than others:

These learners tended to dominate discussions and make most of the decisions regarding the task, thereby resulting in a non-collaborative atmosphere. In these groups, there was far less social talk among group members, and the tone of conversation was more serious and matter-of-fact. When there were misunderstandings between group members, they were often resolved in an inequitable manner as the enforcer of the English-only policy would typically have the final say in the conversation. (p. 17)

Speaking of these times, other students complained to Rajendram that one person (e.g., Kamini, Suren, Yashwin) was dominating the group and that some people who “had talent” but couldn’t express themselves as well in English were sidelined (p. 17).

Moreover, there were wider discourses in society about “native speakers” that negatively affected teacher and parent views of translanguaging. Ms. Shalini told Rajendram that she did not feel confident in her own English, but believed that by requiring students to speak English, she could help them build confidence. Rajendram reports that “several learners complied with her English-only policy because they felt it was meant for their own good” (p. 17). For example, Yashwin told Rajendram “we must know how to speak English fluently” (p. 17) to explain why Ms. Shalini scolded them for speaking Tamil. He also appeared to believe, because of what his father told him, that language correlated simply with audience: “My father said Tamil means you can speak with all the Tamilians, and then Malay means we can speak whole of Malaysia, but English means we can speak international” (p. 19). Kamini, a fifth grader, shared in an interview, “I want to marry an American” (p. 19). In addition, although Rajendram noticed students using bilingual dictionaries under their desks, they told her this action made them feel they were doing something wrong (p. 18).

Finally, students were also subject to negative positioning with regard to their Malay. They were aware of balik Cina, balik India discourses that tell Chinese- and Indian-Malays to go back to their “home” countries (Singh, 2013). They knew they would need to speak Malay in the future for university and white-collar employment, although interview data suggested that they did not consider it to be their own language. In fact, some felt they would never be able to speak in “normal Malay” because of the transfer from other languages or because they were not Malays, and were anxious that any sign of crosslinguistic transfer would invite bullying from Malay people, which reduced their motivation to speak Malay. As one student said: “I don’t like Malay because if you tell the wrong word to the Malay people, they will bully us, tease us like that. If we say something wrong, they will keep in their heart, ‘These Tamil people don’t know how to speak Malay’ like that” (p. 20). Rajendram concludes:

These findings highlight the importance of recognizing that although translanguaging should ideally involve the use of learners’ linguistic repertoire without regard to individual named languages, this ‘does not mean that the learner is not aware of the political connotations or the structural constraints of specific named languages’ (Li Wei & Ho, 2018, p. 35). … Thus, teachers need to be critically aware of the complexities of learners’ language choices and the political and social constraints to translanguaging, so that they can work with learners to mobilise all their language practices despite those constraints. (p. 21)

Conclusions

Language use is always deeply embedded in a sociocultural milieu (Walqui, 2006), and thus translangauging researchers “need to carefully consider the distinctive features, affordances and constraints of translanguaging in any given context” (p. 22). It is not simply a matter of empowering learners to access all their language resources but of helping learners “learn to do translanguaging” (Garcia & Lin, 2016, p. 132). In fact, learners must also be included in explicit discussions of barriers to translanguaging—“historical, cultural, ideological, political, and social factors influencing their language use” (p. 23)—so that they can potentially act in different ways. For them to be fully empowered, Rajendram argues, teachers need to help them interrogate their implicit as well as explicit biases. These discussions should extend to parents, because it helps when home discourses support rather than contradict the development of critical language awareness.

As for Ms. Shalini, fortunately, after seeing the evidence from Rajendram’s dissertation on the affordances of translanguaging, she began moving away from her English-only policy. Similar to Hamman (2018), Rajendram argues that “an effective translanguaging pedagogy should be a two-way, dynamic and participatory process that is both teacher- and learner-directed. While teachers should be intentional in designing strategic lessons based on the principles of translanguaging, these should be informed by and responsive to the ways that learners naturally and spontaneously use their translanguaging repertoires” (p. 24)—the good and the bad. In this way, teachers can plan pedagogical activities that raise students’ awareness of their language practices and ideologies, and of their metalinguistic and metacognitive strategies, and make it more likely that they will translanguage agentively in other contexts… including ones in the future that are less favourable to translanguaging.

References

Allard, E. C., Apt, S., & Sacks, I. (2019). Language policy and practice in almost-bilingual classrooms. International Multilingual Research Journal, 13(2), 73-87. https://doi.org/10.1080/19313152.2018.1563425

Canagarajah, S. (2011). Translanguaging in the classroom: Emerging issues for research and pedagogy. Applied Linguistics Review, 2(2011), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110239331.1

Fairclough, N. (1995). Critical discourse analysis. Longman.

García, O., & Lin, A. (2016). Translanguaging and bilingual education. In O. García, A. Lin, & S. May (Eds.), Bilingual and multilingual education (pp. 117–130). Springer.

Hamman, L. (2018). Translanguaging and positioning in two-way dual language classrooms: A case for criticality. Language and Education, 32(1), 21-42. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2017.1384006

Leonet, O., Cenoz, J., & Gorter, D. (2020). Developing morphological awareness across languages: Translanguaging pedagogies in third language acquisition. Language Awareness, 29(1), 41-59. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2019.1688338

Li Wei, & Ho, W. Y. (2018). Language learning sans frontiers: A translanguaging view. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 38, 33-59. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0267190518000053

Lin, A. (2016). Curriculum mapping and bridging pedagogies. Language across the curriculum & CLIL in English as an Additional Language (EAL) contexts: Theory and practice (pp. 77-110). Springer.

Malaysia Department of Information. (2017). Demografi penduduk [Demography of population]. https://www.malaysia.gov.my/portal/content/30114?language=my

Mercer, N. (2004). Sociocultural discourse analysis: Analysing classroom talk as a social mode of thinking. Journal of Applied Linguistics, 1(2), 137–168. https://doi.org/10.1558/japl.2004.1.2.137

Rajendram, S. (2019). Translanguaging as an agentive, collaborative and socioculturally responsive pedagogy for multilingual learners. PhD dissertation. University of Toronto.

Singh, R. (2013, August 5). The real problem in ‘balik Cina, balik India’ not solved. Malaysia Today. https://www.malaysia-today.net/2013/08/05/the-real-problem-in-balik-cina-balik-india-not- solved

van Lier, L. (2008). Agency in the classroom. In J. P. Lantolf & M. E. Poehner (Eds.), Sociocultural theory and the teaching of second languages (pp. 163–186). Equinox.

Walqui, A. (2006). Scaffolding instruction for English language learners: A conceptual framework. The International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 9(2), 159–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050608668639

Woodley, H., & Brown, A. (2016). Balancing windows and mirrors: Translanguaging in a multilingual classroom. In O. García & T. Kleyn (Eds.), Translanguaging with multilingual students: Learning from classroom moments (pp. 83-99). Routledge.

World Atlas. (2018). What languages are spoken in Malaysia? https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/what-languages-are-spoken-in-malaysia.html

4 thoughts on “The translanguaging paradox: How students translanguage while using distinct languages”

Comments are closed.