This is the second of 3 blog posts summarizing a book by Prof. Ann Burns on Action Research (AR) in language teaching. In my previous post, I summarized the first part of the book, on what action research is. In this post, I provide a summary of the middle of the book, on how to conduct action research by collecting four main types of data: observations, interviews, questionnaires/surveys, and documents.

Burns, A. (2010). Doing action research in English language teaching: A guide for practitioners. Routledge.

Chapter 3: Act – putting the plan into action

Burns shows that Action Research (AR) doesn’t need to be complicated to understand or intellectually exclusive, but it does require a research mindset, in that you need to think about what kinds of data you need to collect, to give you a valid picture of what you want to know. This is what Chapter 3 of the book, “Act – Putting the plan into action” is about. Burns first talks about collecting data from classroom activities, then collecting data through four main sources (observations, interviews, questionnaires/surveys, and documents), and lastly discusses how to put different data sources together to strengthen the evidence (called “triangulation“).

Collecting data from classroom activities

The things that normally happen in class generate data quite naturally. Burns gives a few examples (p. 55):

| Classroom activities | Data |

| Teaching grammar | Audio-recordings of whole-class or small group interactions to see how students are practicing the grammar |

| Teaching writing | Collect students’ texts over a period of time and monitor the improvements and remaining gaps in their writing |

| Utillizing different materials | Interview or have focus groups with students about their thoughts on the materials compared to previous materials |

| Teaching vocabulary | Give students a questionnaire about their responses to different vocabulary activities |

| Autonomous learning | Ask students to journal about their most effective strategies for learning |

| Motivation | Get students to interview one another about the extent to which they like different classroom activities and report back |

These are just some possibilities. As mentioned in the previous post, students will often be happy to participate in classroom research, or even be co-investigators, if the problem or issue to be investigated interests them as well.

A key point Burns makes in her introduction is that you need to collect the forms of data that can answer your research question. For example, if you want to know why students choose certain vocabulary over other vocabulary in their writing, just collecting their writing samples won’t do—you need to interview them, or even audio-record their thinking aloud during the writing process. Similarly, you can’t just ask them what they said during a speaking activity, but need to audio-record the activity. However, there is a “cost effectiveness” to data collection; you must “choose manageable and doable techniques that you are comfortable with and do not take excessive amounts of time” (p. 56).

You can also have a colleague observe the class with a focus on particular things. Or you can make diagrams that trace patterns of interaction in the classroom, or have students turn in portfolios of work that they’re proud of. That is to say, even if you are a teacher whose time is limited, AR involves effortful and systematic data collection to really see what is going on in your class.

Observations

The purpose of observations is to make familiar things strange, to see things you haven’t noticed before, becoming a stranger in your classroom and asking things like: What is REALLY happening here? What social roles are people taking up? What happens if I change the set-up or communicate differently? What will students do if I give them new choices? (p. 57). Burns reminds us that AR is different from routine thinking about the class because you have a specific research focus, are trying to investigate that thing objectively rather than giving in to personal intuition or bias, and are continually re-evaluating your interpretations by sharing the data with others.

Observations give rise to several questions:

- Who/How many will you observe? Everyone? Focus on some participants? Why?

- What/Where? What will you observe, and how will you position yourself (or the recording device) to do so?

- When/How often? You may not need to observe or record all of a lesson, depending on your focus. It is also necessary to consider how many times you will observe the same activity (e.g., show and tell, jigsaw sharing, peer review, etc.) to be able to answer your research question with sufficient data. Sequencing may be important in some cases—for example, when testing the effects of a practical intervention.

Keep in mind that observations may NOT be necessary for your research question—indeed, any kind of data may be useless for a particular question. For example, if you want to know about students’ vocabulary growth when doing extensive reading, it is likely not going to be useful to observe them reading, but to assign periodic assessments and have them keep reading logs of what and how much they read. Or if you want to know what students’ views are of speaking tasks, you may not need to observe them doing the tasks, but to interview them or administer questionnaires about the tasks.

Some famous researchers have published observation protocols for large-scale research, such as COLT (Fröhlich, Spada, & Allen, 1985) and SIOP (Echevarria, Vogt, & Short, 2012). The purpose of their guides is to make sure that teams of researchers observe in a uniform way. These observation protocols can be quite sophisticated and extensive, and if you are interested in learning how to use them, Burns suggests reading the books by the original authors. However, more likely, something much simpler will suffice for your purposes. Remember not to make your observation protocol too extensive, or you will end up with “too much to look for in too little time” (p. 63). The example Burns gives is the behavior checklist (Mendoza López, 2005), which is basically just a grid with about ten behaviors that you (or your colleague) need to memorize/become familiar with before observing:

| Teacher questions | 10:09 | 10:10 | 10:15 | 10:18 | 10:20 |

| Silence | 10:15 | ||||

| Pupil response | 10:09 | 10:10 | |||

| Pupil question (related) | 10:10 | 10:16 | 10:18 | ||

| Pupil question (unrelated) | 10:19 | ||||

| Etc. |

This can show what things happen in class, when they happen, what is common or rare, and what the class gives priority to.

It is possible to fill in your observation protocol not while watching the class, but based on a recording, which has the advantage of being able to be played back. And Mendoza López’ behavior checklist is only one of an infinite number of protocols you can use to investigate just about anything. Here is one of mine (I am not Mendoza López) on turns involving Filipino versus English talk in a 9th/10th grade ESL class in Hawai’i (Mendoza, 2023, p. 103):

I originally tallied the instances while listening to a recording, then changed them to numbers. This had to be triangulated with interviews since I could only capture the behavior, not reasons for it.

Another behavior checklist (Al-Fahdi, as cited in Burns, 2010, p. 66) allows a researcher to note what kinds of feedback they gave in class: evaluative (“good”, “yes”, “OK”, “thank you”), corrective (e.g., Student: “A limp” Teacher: “A lamp”) and strategic (reminding learners to monitor and check themselves: “Remember to use plural verbs for plural nouns”):

| Task 1 | Task 2 | Total | |

| Evaluative | 23 | 25 | 48 |

| Corrective | 8 | 6 | 14 |

| Strategic | 5 | 3 | 8 |

Something to consider is reliability, or whether someone else would get much the same results. That is, descriptions of categories should be clear enough for someone else to know what they mean, and they must be objective enough not to rely too much on personal judgment (we call this “low-inference” versus “high-inference” coding).

During or after completing an observation protocol, you’ll want to write observation notes, which can be reflective or analytical. Reflective notes simply report what is happening, and you’ll want to write enough of these before jumping straight to analysis. These notes are typically written in the margins of the observation protocol, or using the Comments function on a word processor. Analytical observations involve higher level analysis. (These two kinds of notes are similar to descriptive and analytical coding in Grounded Theory.) When we analyze, we start to interpret what we see. Do we need other sources of data to determine the most plausible interpretation?

Then there are narrative observations, which recount what is happening. An example that I’ll include here (not from a classroom but a marketplace in the UK) is from Blackledge and Creese (2017):

You may need to use shorthand, e.g. T for teacher, Ss for students, etc. to be able to do this fast enough. Then, the last and most general type of observation is called shadowing, where you watch the whole event/class first and then write some notes immediately afterward. This approach is used in classic Grounded Theory, called memos.

Burns discusses how to transcribe talk next, but instead of summarizing that, I’ll point to a more detailed discussion about verbatim versus intelligent verbatim (two main choices) in my post on Grounded Theory.

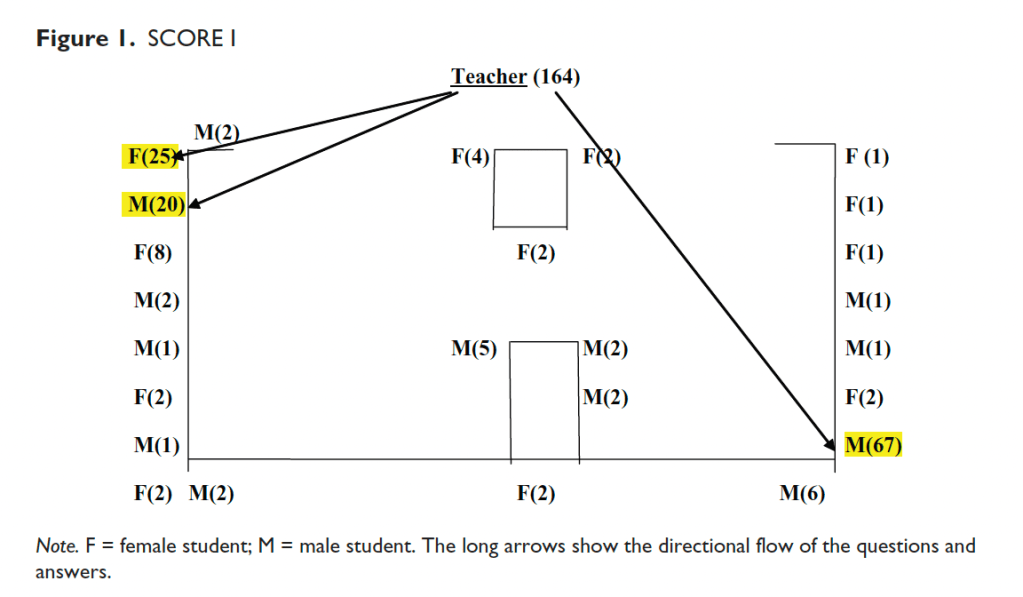

The last consideration in observing is the importance of classroom mapping. Visuals can be powerful, reminding us of where things happen, where people are, or how patterns of behavior emerge. They can capture the social dynamics of a class. That said, maps often tell us troubling things. For example, they can tell us that class participation is unequal among individuals and genders (Farrell, 2011, p. 268):

They can tell us that newcomer immigrant students and long-time local residents can segregate themselves from each other (Duff, 2002, p. 299):

An example that has stuck with me (though I don’t remember what paper or talk it was) was about Uyghur students in a university in China. The researcher captured several snapshots over time and showed that not only did they sit at the back of the lecture hall, but their attendance dwindled over time as they apparently felt isolated and gave up.

Where do people position themselves? Who likes to work together? Who is “liked” or “disliked”? (p. 72) These are important factors that impact how teaching and learning goes.

Interviews

Without interviewing, you cannot get into other people’s thoughts, beliefs, and perceptions, or their personal histories and rationales for their actions. Interviews are “conversations with a purpose” (Burgess, as cited in Burns, 2010, p. 74). Most interviews are semi-structured, in which

you have a set of topics in mind that you want to explore and you may also have developed some specific questions, but you will allow for some flexibility according to how the interviewee responds. For example, you may want to ‘probe’ to get more details about some of the answers that crop up or make allowances for unexpected responses that will lead you into new discoveries. (p. 75)

The semi-structured interview feels more conversational than a structured interview with no chit-chat (people stick to a closed set of responses). Structured interviews are appropriate for marketing survey research but not education research. On the other hand, there are open-ended interviews in which you let the interviewee talk at length after giving them a single prompt, such as:

A lot of people think of their lives as having had a particular course, as having gone up and down. Some people think it hasn’t gone down. Some people see it as having gone in a circle. How do you see your life? Which way has it gone? (Holstein & Gubrium, 1995, p. 9)

A study by the great sociolinguist William Labov compared White American and African-American dialects, proving that they were both grammatical and that African-American English was not an ungrammatical form of English. This was also a pioneering narrative analysis study, outlining universal aspects of narrative structure. It used an open-ended prompt: he asked people if they had ever been in a situation in which they thought they would die (Labov, 2010).

In my research, I have used open-ended prompts in teacher background interviews (Mendoza, 2023), to simply ask for their life stories starting around university, when they first got into teaching—that is, what led them to become teachers and how they got into their current jobs. Burns makes an important point about semi-structured and unstructured interviews (p. 77):

Although it sounds as though they don’t need much preparation, these kinds of interviews are actually the most demanding. They require a high level of trust between interviewer and interviewee and careful handling because of the unpredictability of the conversation. It’s unlikely that you will be able to make comparisons across your interviews [compared to structured ones]… because of the highly individualized nature of the responses. Also, while the information you gain will probably be rich and may give you unexpected insights, it needs a cautious and sympathetic analysis. (p. 77)

In addition to deciding whether to conduct semi-structured or unstructured interviews (or both), when, and why, you will need to decide whether you will do individual interviews or focus groups (or both). The advantages of individual interviews are confidentiality and freedom to say what one wants to say without peer pressure. The advantages of focus groups are that people can get excited and generate rich ideas based on one another’s remarks; however, some individuals can hog the spotlight and keep others from speaking freely. To decide which you want to do, you need to ask yourself if what you are researching is what the group generally agrees on, and the processes by which they come to this agreement… or what individuals think.

You will also need to decide whether you will audio-record or just take notes, and what you will use to take notes. Audio-recording can make people uneasy, as there is a verbatim record of what they say, in their voices… but then again, the interviewer taking notes while they talk can also make them uneasy (in my view, this is especially so with a laptop, which makes fast clicking sounds as the researcher types, and less so with a notebook or audio-recorder). Oftentimes audio-recorders (and Zoom recording functions) disappear into the background and people forget about them unless what they are recording is sensitive. Consent forms often state the interviewees can ask the researcher not to use some of the data.

When preparing to do interviews, it is often a good idea to get feedback from professors or colleagues on your interview questions. Other considerations (Richards, as cited in Burns, 2010, p. 78-79) include:

- The timing and order of interviews (order can be influential to the study, even if coincidental, because what some people say may influence what you ask other people),

- The location of interviews—Burns says to choose places that are “appropriate, comfortable and attractive” (p. 78) to put the interviewee at ease, but not places that are too loud to get a clear recording, such as a coffee house or busy cafeteria. The interview may need to take place in a private office or empty classroom if the topic is more personal.

- The length of time—30 minutes to an hour is most appropriate, enough to get the details you need, and people get tired with longer interviews.

- The ethical considerations—obtaining consent and telling the interviewee what you will do with the data, and promising to check the information with them later.

Burns gives her own advice on interviewing well (p. 79):

- Give the interviewee enough time to answer, even if there are moments of silence.

- Start with friendly chat and warm-up questions to break the ice.

- Start with open questions that are not face-threatening and encourage the interviewee to talk at length. These are how, what, why, when, and where questions such as “What kinds of books do you like to read?”

- When clarifying, be explicit about what you are trying to accomplish, by saying things like: “Can you give me an example…” (that is, you want concrete examples), or “So to summarize, I think you’re saying that…” (that is, you’re seeking the overall idea). In this way, you explicitly seek the interviewee’s alignment with your emerging interpretation—you don’t unintentionally come up with your own details or your own summary of key points without their verification.

- Always end with: “Is there anything else you’d like to add? Is there anything else I should have asked you about this?” Burns notes: “Sometimes these kinds of questions can result in a surprising amount of extra information” (p. 80)—sometimes the best information, in my experience!

Questionnaires/Surveys

Questionnaires are more helpful than interviews for making direct, clear comparisons between individuals. Dörnyei (as cited in Burns, 2010, p. 81) defined three types of questions: factual/demographic (How many years have you been teaching?), behavioral (When did you start implementing peer review in teaching English 100?) and attitudinal (What do you think about the native speaker standard?). You can also present things as statements or questions. For example, for a behavioral question, you can say, “How do you teach new grammar tenses?” Or “I teach grammar tenses through implicit exposure, such as songs and poems.” Burns notes that the way the questions are phrased leads to different kinds of responses. For example, the question about teaching grammar is open-ended, but when turned into a statement it narrows down the question to a specific practice and the respondent has to rate it on a Likert scale, perhaps with 5 being “all the time” and 1 being “never.” Some questions ask for concrete facts, others suggest a choice from a range of possibilities, some invite yes/no answers, and some elicit a longer, more personal response (p. 82).

Overall, closed-ended questions can be:

- Yes/No

- Rating/Likert scales (strongly agree to strongly disagree, or always to never); these are often 5-point, but can be 4-point (forcing the respondent to lean one way over the other… and I am sure there have been tons of debates on pros/cons of having the neutral option)

- Multiple choice, which can require the respondent to choose only one option, or to “tick all that apply”

- Rank order items, in which what the researcher is interested in is the rank rather than extent of importance. This approach is used in Q-methodology surveys. For example, you might ask, “Please rank in order of most to least difficult for you when writing: finding a topic, researching the information, making a plan or outline, deciding where different information should go, or developing the arguments.” However, be careful not to include too many items as it will be difficult for participants to order them. This approach is used when what you want to know is what people prioritize, not the degree to which they care about each thing. For example, I may rank “finding a topic” the least difficult, but I could still find it difficult.

Open-ended items are free-form responses and can be similar to interview data in that there are different levels of potential guidance. For example, you can ask the open-ended question, “Is there anything else I didn’t ask about that you would like to say?”, just like at the end of an interview. As in interviews, guided questions can be asked to probe further: “If you rated your students’ tendency to care about grammar accuracy as Rarely or Never, please explain.” Additionally, if you have a multiple choice question with an “Other” option, it can have a box saying, “Please explain.” There are also sentence-starters, such as: “The most challenging thing about this class is…”

When laying out a questionnaire, Burns recommends the following skeleton:

- Title of project

- Researcher [and contact information]

- Purpose of project: What it aims to do/find out, and what outcomes are expected

- Brief instructions for filling out the questionnaire

- Approximately how much time it should take to fill in

- Items

- Other information, e.g., contact information [I suggest having that up top, by the researcher’s name]

- Ethical statement or indication of confidentiality of responses

- A statement of thanks to the respondent, and a smiley emoji 🙂

Burns recommends trying out questionnaires on colleagues to see how easy they find it to answer the questions. Get feedback on what can be changed to make the questions as clear and user-friendly as possible. You can also get feedback on whether people think the questionnaire is too long, or if it doesn’t let them fully express what they want to (and if so, what closed- or open-ended questions can be asked). Burns reminds us that

Designing a questionnaire may sound easy—and indeed it may be the first method that comes to mind when you think about doing research—but it needs some careful thought and planning if you are to get the information you need in a useable form. There is a lot of trial and error involved in getting to a good final version so to make sure you get the answers you want you should pilot the questionnaire before using it. This means trying it out on the type of participant who is likely to be answering it, but who won’t eventually be involved in your research. (p. 89)

Piloting typically shows you the following errors: questions are ambiguous, they are too convoluted, they require background knowledge the respondent doesn’t necessarily have (e.g., specialized terms), they are not appropriately written for the respondents’ age (such as children), proficiency in the language the questionnaire is in, or literacy level. You may consider administering bi/trilingual questionnaires like we did in Mendoza, Ou, Rajendram & Coombs (2023).

We piloted the question item and the example in English with dozens of individuals, then my colleague Jiaen Ou translated the example of each question into Cantonese and Mandarin. We provided concrete examples of each behavior question regarding 30 ways that teachers could draw on students’ existing languages to learn additional languages, so that teachers could clearly see what we were talking about.

Burns points out that you can get some way in sorting out problems with your questionnaire if you do so much as try to answer it yourself (p. 89).

Journals and logs

Journals are unlikely to provide useful data in themselves, but are useful for “capturing significant reflections and events in an ongoing way” (p. 89). For example, you can write memos immediately after the lesson/events so things are fresh in your memory. You can capture, in stream-of-consciousness, your feelings and responses. A daily or weekly log can allow you to compare how things went at multiple time points, and a memoir-style diary can allow you to articulate your values and theories as a teacher, who or what influenced your development.

Classroom documents

Classrooms are full of written documents, any of which can be data. You can collect copies of students’ writing and study how they develop over time. [Blogger’s note: It is best to give them feedback on what you are noticing and/or to teach some of the things you find many students are lacking so that they gain something.] You can collect your lesson plans to analyze what skills/activities you tend to focus on, thinking about the strengths, weaknesses, and patterns in your teaching. You can allow your students to put together portfolios of their best work, choosing what they will include, and work with them to identify some obvious signs of learning in these documents, which can be encouraging to them. Burns notes that these days, portfolio assessment and student self-assessment have become popular ways of tracking student progress in partnership with students and diagnosing areas for further development, as a valuable alternative to more traditional forms of assessment.

Documents can be electronic. Journals can be web-based, such as blogs. Likewise, interviews and focus groups can take place on discussion boards or on Zoom. Some can even take place in virtual reality (VR) environments.

Cross-checking and triangulating to strengthen the data

One common criticism of action research, and qualitative research in general, is that it can be too subjective. Cross-checking and triangulating the data helps it establish credibility.

The term triangulation comes from astronomy. People navigating the wilderness or the oceans took different bearings and measurements to make sure a particular location was accurate (Bailey, as cited in Burns, 2010, p. 95).

If we apply this to data collection it means that a combination of angles in the data will help give us more objectivity. This usually means collecting more than one type of data (it doesn’t necessarily mean three types, although the term triangulation seems to suggest this). Then you can compare, contrast and cross-check to see whether what you are finding through one source is backed up by other evidence. In this way you can be more confident that your reflections and conclusions are supported by the data and not just by your own presuppositions or biases. (pp. 95-96).

However, one misconception about triangulation is that it only applies to collecting multiple types of data. In fact, there are many different kinds of triangulation (Denzin, as cited in Burns, 2010, p. 97):

- Time triangulation, in which data are collected at different points in time, for example throughout a course.

- Space [or group] triangulation, in which data are collected with different groups of people, for example, an intervention is tried with more than one class, or parents are interviewed as well as students.

- Researcher triangulation, in which data are collected by more the one researcher, to mitigate the biases of individual researchers.

- Theory triangulation, in which data are analyzed from more than one theoretical perspective.

The benefits of triangulation are obvious: from getting a more rounded/balanced perspective from a wider range of informants (or a co-researcher), to inviting more complexities and contradictions for a richer theory.

But it can also appear daunting if you are not used to collecting so much data… It can mean doing a more radical assessment of your own biases as new insights emerge from different sources. This experience can sit uncomfortably at first and seem a bit threatening. The best advice I can offer is to be aware of how triangulation can help to make your research stronger and richer, and to adapt the idea of triangulation to suit the time, energy and resources you have available. (p. 97).

Summary

Johns says, “Please bear in mind that the ideas I’ve presented [for data collection] are not exhaustive. By building on some of these methods, you may be able to think of any number of original and exciting ways to collect data that will answer your questions” (p. 97).

She also says: “Don’t be discouraged, either, if some of your attempts at collecting data don’t always go the way you intended or fail to give you the results you wanted or expected” (p. 97). Burns cites Weathers (2006), who gives an honest account of how multiple data collection sources failed. Her tape recordings turned out to be poor, and her friend Ying, who observed the class, had difficulty completing the observation protocol because students spoke at the same time and she could not get a good view. In the end, Weathers adapted by interviewing Ying and the students themselves about their impressions of the lessons, and chronicling her perceptions in her teaching journal. [Blogger’s note: While the adaptation did not offer the same insights as recordings or a structured protocol, it had other advantages. I cannot see how it could fail to engage the researcher, her colleague, and the students in thoughtful collaborative discussions, potentially leading to improved actions.]

In the last part of the book, Burns considers how to analyze the data collected from action research and apply the results. Stay tuned for part 3 (the last part) of this 3-part blog post summarizing her informative and student-friendly handbook on action research!

References

Blackledge, A., & Creese, A. (2017). Translanguaging and the body. International Journal of Multilingualism, 14(3), 250-268. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2017.1315809

Duff, P. A. (2002). The discursive co‐construction of knowledge, identity, and difference: An ethnography of communication in the high school mainstream. Applied Linguistics, 23(3), 289-322. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/23.3.289

Echevarria, J., Vogt, M., & Short, D. (2012). Making content comprehensible for English learners: The SIOP model (4th ed.). Pearson.

Farrell, T. S. (2011). ‘Keeping SCORE’: Reflective practice through classroom observations. RELC Journal, 42(3), 265-272. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033688211419396

Fröhlich, M., Spada, N., & Allen, P. (1985). Differences in the communicative orientation of L2 classrooms. TESOL Quarterly, 19(1), 27-57. https://doi.org/10.2307/3586771

Holstein, J. A., & Gubrium, J. F. (1995). The active interview. Sage.

Labov, W. (2010). Oral narratives of personal experience. Cambridge encyclopedia of the language sciences. https://www.ling.upenn.edu/~wlabov/Papers/FebOralNarPE.pdf

Mendoza, A. (2023). Translanguaging and English as a lingua franca in the plurilingual classroom. Multilingual Matters.

Mendoza, A., Ou, J., Rajendram, S., & Coombs, A. (2023). Teachers’ awareness and management of the social, cultural, and political indexicalities of translanguaging. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2023.2263092

Mendoza López, E. (2005). Current state of the teaching of process writing in EFL classes: An observational study in the last two years of secondary school. Profile: Issues in Teachers Professional Development, 6, 23-36. http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?pid=S1657-07902005000100003&script=sci_arttext

Weathers, J. (2006). How does course content affect students’ willingness to communicate in the L2? In T. S. C. Farrell (Ed.), Language teacher research in Asia (pp. 171-184). TESOL International Association.

One thought on “Doing action research in English language teaching (part 2 of 3)”

Comments are closed.