This post continues the previous one on the qualitative methodology called Grounded Theory (GT). I summarize the second half of the textbook on GT in applied linguistics by Prof. Gregory Hadley at Niigata University. This half contains a practical guide on how to do GT. It has four parts: (1) setting up your study, (2) lower-level/descriptive coding, (3) higher-level/analytical coding, and (4) writing up the study.

Hadley, G. (2017). Grounded theory in applied linguistics research: A practical guide. Routledge.

Chapter 4: Preliminary decisions and setting up the study

This chapter is about (1) research ethics (particularly IRB study applications that you have to submit to your university research ethics board before you can begin the research), (2) gaining access to the research site, and technical things like (3) transcriptions, and (4) qualitative analysis software.

Research ethics involves “informed consent, avoidance of deception, protection of privacy/confidentiality, and accuracy of reporting” (Christians, 2000, as cited in Hadley, 2015, p. 67). Informed consent means people choose to participate in the study after being given all the information necessary to make that decision (avoidance of deception). Privacy means protecting participants as they’re participating in the study, and confidentiality means protecting the information gathered from them. The last thing, accuracy of reporting,

means being faithful to what was reported by informants, being fair to the multiple perspectives portrayed, and insuring that the theory is a plausible explanation for what is taking place in the research domain. (p. 68)

[Blogger’s note: In my view, this is the one most easily flouted, because it does not directly hurt participants, they will not complain or come after you, and your university research ethics board cannot easily police “accuracy of reporting.” There is no question on how you will accurately report results in an IRB study application like there is about informed consent, privacy, and confidentiality. But inaccurate reporting can have negative consequences for an academic field and for society, and that is why I think GE principles can inform qualitative research more broadly on how to do this better.]

Hadley points out that IRB applications tend to protect universities, not researchers, nor participants, and are most concerned with bureaucratic procedures or even censoring research that could threaten the reputation of the university (p. 73), even if the research is not harmful. To be your own ethical guide, consider what projects similar to your own have taken place in the past. Have they had any problems in the past when a person/people were harmed, and if so, how? Hadley provides a valuable reference—Sieber (1992)—a famous book about ethical qualitative research. This book gives good advice such as how it’s more important to consider people rather than protocols. (For example, a protocol may demand written documentation of consent. But is this really the most ethical option in all cases? Sometimes written forms intimidate participants, such as young children, those with limited formal education, or those for whom such forms are culturally inappropriate. In this case, it may be best to provide participants with a written description of the project in lay language that they can refer to in their own time, and obtain oral consent instead.)

The silver lining to IRB applications, Hadley explains, is that they can help you develop a clear idea of what you want to do, and are a test of whether you can articulate that clearly (p. 76). Remember, you can initiate dialogue with your university’s IRB department about what is most ethical for your participants—”people over protocols.”

When it comes to gaining access to your research site, consider power dynamics very thoughtfully. Even if you research places where you have existing personal or professional connections, participants’ willingness to talk “will depend on whether potential informants see any benefit in working with you. Similarly, failure in convincing people to open up is often related to any risks they see in talking to you” (p. 78). If participants have a lot less power than you (such as students and teachers), they may sign the consent form without delay, but resist by saying little. If participants have a lot more power than you (such as administrators) they may also sign the form, but use their written consent as leverage to make sure they are pleased with the findings of your research (p. 78). Then there’s the situation where you feel that everyone is on your side and happy to give you lots of good interview data—but this can “skew your grounded theory, since your work might lack adequate levels of constant comparison” (p. 79)—you all have the same views. How do you deal with such problems? Hadley points out that Strauss and Corbin had them too, as we all do, and says that’s life (p. 79). [Blogger’s note: Seriously, it’s important to build trust with teachers and students and get them to open up. Your research is for them, not for the institutional reputation, nor getting everybody to agree with the latest educational slogans and trends.]

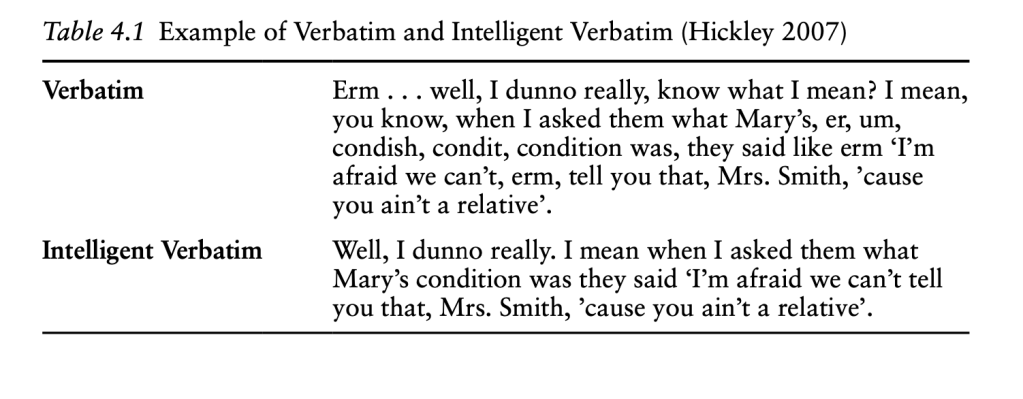

Hadley then goes on to talk about how to transcribe interviews and analyze them. All GT uses interview transcripts, for which you need recording devices as “documentary evidence of your research” (p. 79). Taking the time to transcribe your data forces you to pay close attention to the words and perspectives of informants, and notice things that flew by too quickly during the interview event. The question is how detailed your transcript needs to be. Part of this relates to the paradigms discussed in my earlier blog post summarizing the first half of Hadley’s book. If you are working from a social constructivist paradigm and you are studying how people negotiate versions of reality, you probably need verbatim transcriptions. However, if you just want a window into people’s beliefs, it may be enough to provide “intelligent verbatim” (Hickley, as cited in Hadley, 2015, p. 81):

This is, of course, your choice as a researcher and depends on what kind of project you are doing—what kind of data will suffice to answer your research questions. A classroom discourse analyst like me has to lean more towards verbatim using Jeffersonian transcription symbols, which Hadley mentions. Importantly, there is no such thing as a “perfect” transcript—what you have is the best you can do given your time and resources (p. 83). You can even design your own transcription system, as long as you can justify your conventions and use them consistently. [Side note: Software such as Otter.ai can transcribe English interviews with relatively high degrees of accuracy. You simply upload the .mp3 file and Otter transcribes it. In my experience, this works well if it’s an interview and not natural classroom data—that is, minimal overlap between people speaking. I add the Jeffersonian features manually to the interview transcript while correcting errors in transcription. For classroom recordings, I have to go 100% manual since Otter doesn’t deal well with translanguaging.]

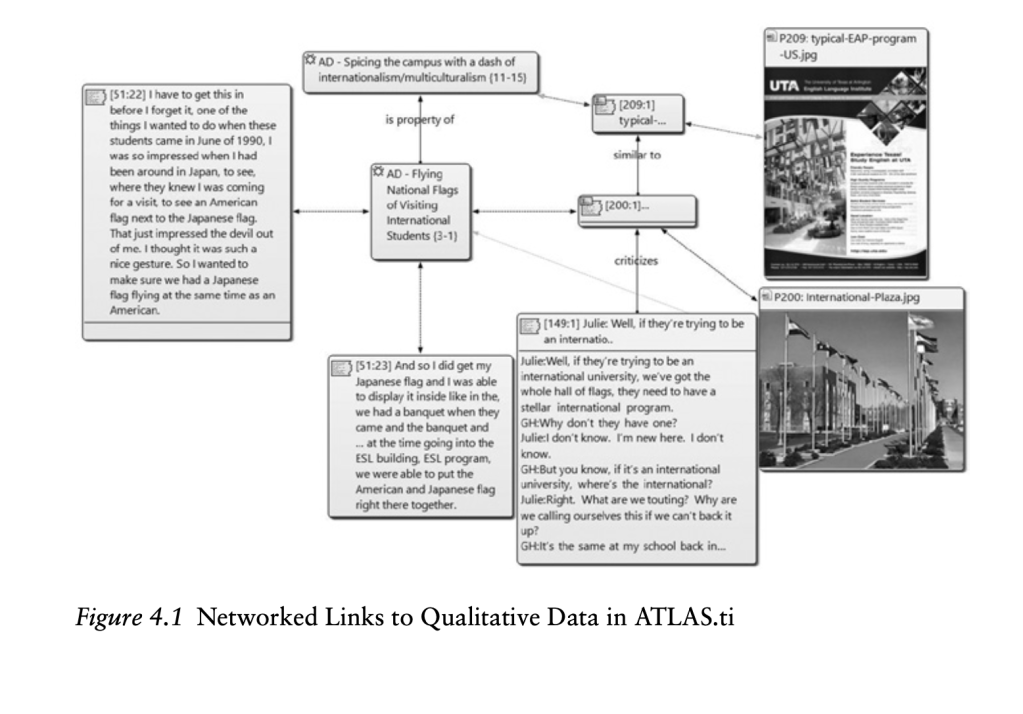

Hadley next discusses software for analyzing/coding your data, which is called CAQDAS (Computer Assisted Qualitative Data AnalysiS). Examples are NVivo (from in vivo codes) and Atlas.ti. Imagine a program that stores all your transcripts, notes, memos, video clips, and photos. When you open the program, you click on the project you want to open—and ta-da! Everything in the project is there. When you click on a code, you can see all the interview excerpts, pictures, videos, etc. relevant to the code. The links to other codes can also be shown.

The advantage to CAQDAS is that your data is searchable and you can work with it in a way that is not possible with simple pen/paper/kitchen table methods, or even word processing software. The disadvantage is that you need to learn your program. It can be expensive—hundreds of dollars—though you can apply for a small grant from your university. Open source programs on the Internet imitate Atlas.ti and NVivo, but personally I don’t know how secure they are.

Hadley states that Glaser did not like CAQDAS (p. 84) because he believed it restricted the development of the theory. Hadley too has found that it can be confining at times, and at those times he prints out material and spreads it out on a table to physically work with the data, which he says has often “helped to broaden my view and stimulate new ideas” (p. 84). The main cautionary note he offers on “to CAQDAS or not to CAQDAS” is that it can be disruptive to switch from one way of data management to another, so carefully consider which one best suits your purposes, and decide before you collect too much data (p. 85).

Chapter 5: Open exploration: lower-level descriptive codes

Open exploration is the beginning of a grounded theory project (once you have gained access to a research site). Remember, stay away from the literature review for now. That comes later. Also stay away from preliminary questionnaires or interviews. While these are often used to preface ethnographies, grounded theory will not permit this—one of the nuances between similar types of qualitative studies.

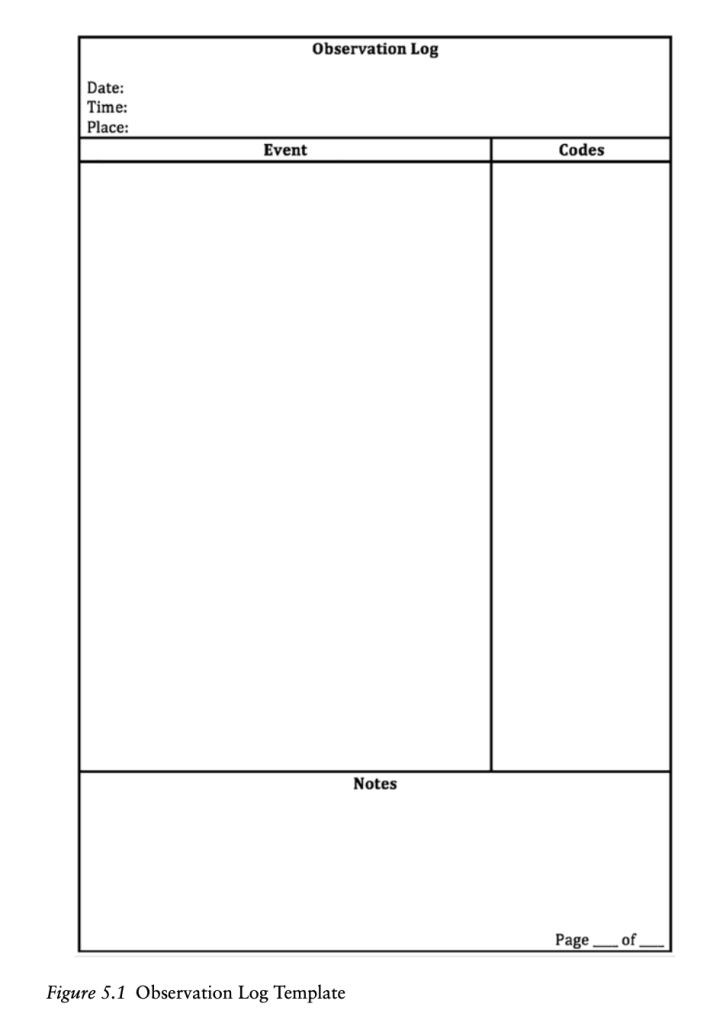

What you start with is observations, using a simple log like this:

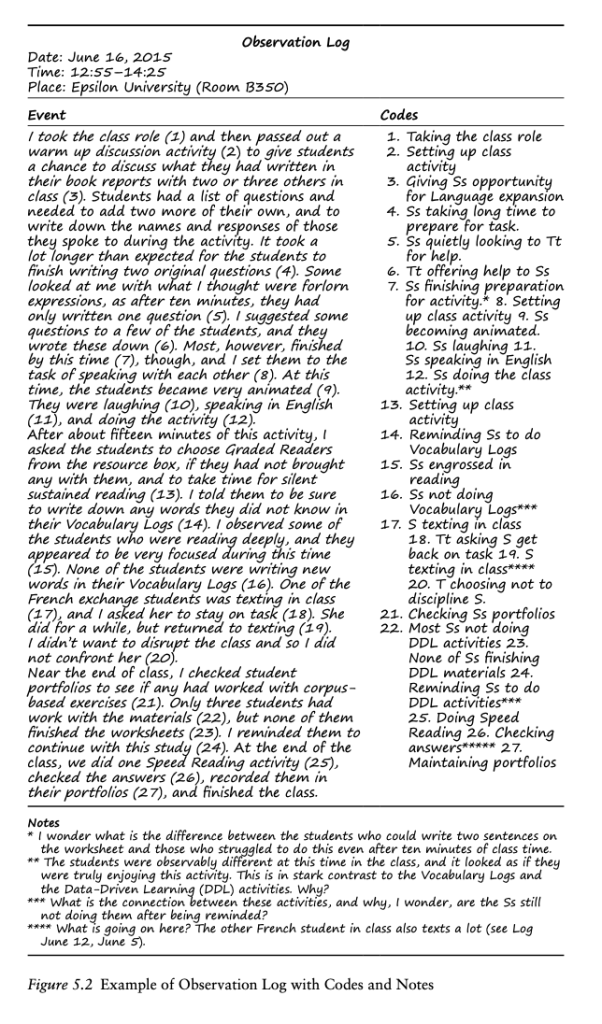

At the end of your observation, it is important to code IMMEDIATELY. Codes can be anything, and there is no right or wrong to coding. Here is Hadley’s example:

These are the first level codes (open/descriptive codes). They should be numerous; many can be ordinary. Beneath, write some notes as to what you notice in particular and wonder about.

(Another way to generate first-level descriptive codes is repertory grids, which Hadley discusses on pp. 91-99, but I will skip them here as they can be quite complex. You can take a look if you want by reading the chapter.)

After observations come interviews. As with observation and coding, people vary in how they conduct interviews, which is natural and expected. A helpful suggestion Hadley gives is to have the interviewee look at the recording device before the interview starts, and have an ordinary conversation about its size, ease of use, etc. This makes the interviewee more at ease with the device:

Talking together about the device before the interview helps to create common ground and to bring the device into the interview, where it will often soon be forgotten. Try to find a quiet setting. Public places such as coffee shops and restaurants tend to be very noisy. There are few things as disappointing as having an excellent interview that is forever lost because of the din of the room. (p. 100)

Like observations, these interviews should be unstructured and exploratory. Some great guidelines for doing qualitative interviews is Holstein and Gubrium’s famous article from the 1990s called “The Active Interviewer”, which Hadley cites in this chapter.

The reason I like this piece is that it shows you how to guide the interviewee—very, very minimally—to generate thoughtful narratives and reflections through ingenious open-ended questions about milestones, crises, memorable successes/failures, etc. In other words, try to ask questions that give the interviewee pleasure to discuss so that they find it emotionally satisfying to participate in your study. Do not question based on theory, e.g., “Attribution Theory suggests that people feel more successful when operating in their locus of personal control. In your class, when do you feel most in control?” (p. 100). This, Hadley notes, would force the informant to discuss something that may not be a pressing concern. It is more appropriate to just ask what would be a good/bad day at work, or what challenges or problems commonly occur in their work and what strategies they’ve used to deal with these. [Side note: Take a look at my other post on conducting multilingual interviews, because language choice can matter.]

As people speak, “Listen to when informants express value statements, because here you can ask slightly more probing questions so that they can further explain what they mean” (p. 100). If informants talk about their values in general terms, ask for specific examples like personal experiences that illustrate the values.

In short, interviews take the shape of something like: (1) ask open-ended questions (really, read Holstein & Gubrium, 1995; it’s short and great and you will become a much better questioner!) —> (2) pay attention to value statements in people’s answers —> (3) probe for specific examples of the value statements, such as personal experiences. Then move to the next topic/question. It is better to ask just a handful of good, well crafted open-ended questions than a long, exhausting list of questions that may or may not lead anywhere and will tire out your interviewee! Moreover, give them time to think. Moments of silence help them organize their thoughts. Tell them that they are very much free to take a minute to collect their thoughts. If they are quiet, resist the urge to jump in and interrupt their train of thought (just as with teaching).

Coding interview data is similar to coding observation data—you can use much the same chart with the transcript on one side, codes on the other side, and notes below. Hadley emphasizes that “Coding will always be idiosyncratic” (p. 103). No one can replicate your study because even if the same informants and questions were there, the data would not be the same the second time around, nor would the coder code the same way.

The notes at the bottom of the coding worksheet can be called “memos.” Here is an expanded version of a memo based on one or more coding worksheets (of interviews and/or observations):

Note the “Future Action” section at the bottom. GT uses “theoretical sampling”—sampling based on the emerging theory, or choosing the next interviewee or context to observe based on what was found in the previous data, like a detective or journalist.

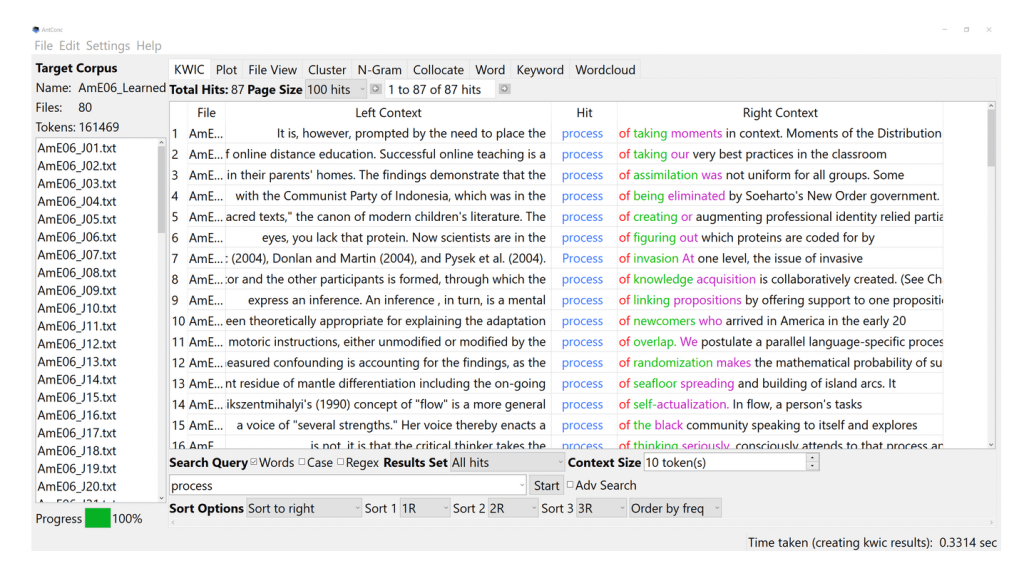

Hadley ends this chapter with a discussion of “in vivo codes”, which comes from Glaser (1978). These are key words or phrases used by informants that crystallize important issues. They often end up in the titles of qualitative studies. For example, in a recently published interview study on English for Academic Purposes, my co-authors and I put: “Only a cog in a machine?: Reappraising institutionalized EAP teacher identities in a transnational context.” For finding in vivo codes that are not cherrypicked from the data, Hadley suggests using simple corpus tools like AntConc (Anthony, 2014), which can reveal the most common collocations and lexical clusters in a file folder full of interview transcripts in .docx or .txt format.

When you feed your interviews into AntConc and ask it to generate the most common words, these will of course be “the”, “be”, “and”, etc., but keep scrolling down until you have meaningful content words. These can be used for constant comparison, as Hadley has done in his research:

For example, using WordSmith Tools, I studied the transcripts of interviews with university English for Academic Purpose teachers, ‘blended’ teacher-managers placed in charge of the programs, and senior university administrators. Constant comparison of the interview wordlists revealed that the higher a person moved up the organizational ladder of universities that had adapted modern business practices for restructuring the organization as a whole, the more that international students recruited for EAP programs were referred to as ‘the numbers’. For those in the organizational positions, the EAP teachers, such lexical markers were never used. Learners were referred to as ‘the students’, especially when EAP teachers wished to use them as a pretext for resisting proposed managerial initiatives that would either drastically change the nature of their daily work or reshape the way they viewed their vocation. The use, or the lack thereof, of ‘the numbers’ among these blended teacher-managers in the middle was one significant indicator of whether they were on an upwardly mobile or sinking trajectory (Hadley, 2015) (p. 106).

While concordance software does not replace the qualitative analysis—“While a comparison of lexical items from wordlists will not serve as a magical workaround for the hard graft of coding, it will reap dividends” (p. 106). As you look at data using concordance software and write memos, you may find your enthusiasm growing; “you will start to see that there is something out there taking shape in the distance” (p. 107). Remember to see-saw between filling in your observation/interview coding worksheets and writing memos. It is not good to do too much of one without enough of the other. Sample —> code —> memo —> purposive sample —> code —> memo —> etc.

Two things that Hadley warns will make you lose your train of thought are: (1) not carrying with you a notebook or cellphone for writing down memos IMMEDIATELY, before you forget them, and (2) talking to someone about your emerging idea before you write it down—as that conversation likely derails the idea. Nothing wrong with talking to the person, just write the idea down FIRST. “Do not worry about grammar, spelling, or proper form. The only real mistake that you can make with memos is not to write them” (p. 107).

Through this process, you will constantly be generating new codes. Editing them is allowed, consolidating, renaming, etc. But this is not where grounded theory ends. When you have a critical mass of data, the higher-level coding begins.

Chapter 6: Taking it to the next level: higher-level analytical codes

This chapter deals with two other types of codes: (1) focused coding, or categories of first-level descriptive codes, and (2) axial coding, or when a code is linked to its causes, contexts, consequences, etc. For example, a focused code might be: “inadequate opportunities to practice target language outside of class” [+ quotes, observations, etc. showing how this is so]. An axial code, on the other hand, might be, “Lily positions herself as the class polyglot (one who knows many languages)” [+ interviews, observations, artifacts collected over time and memos about causes, contexts, consequences, etc. of Lily doing so].

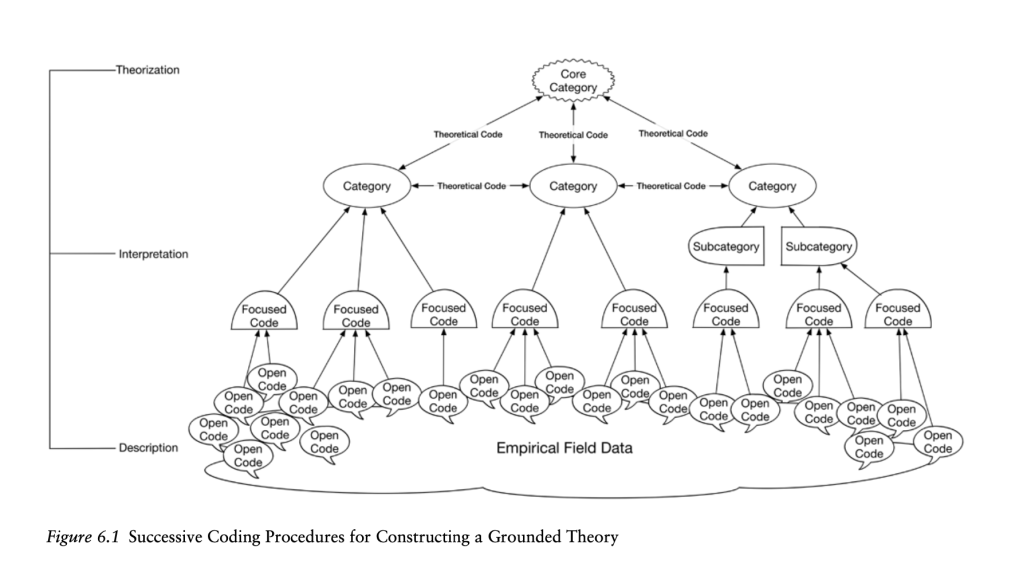

Axial codes and focused codes give rise to the next level up, conceptual categories, which are abstract concepts. Several conceptual categories give rise to the core category or phenomenon, which is the grounded theory, i.e., “The theory of ____.”

Hadley starts this chapter with focused codes. This simply entails grouping similar descriptive codes together. In Word, you can copy/paste the codes under headings and easily sort/move them. If doing it manually, put cue cards or (cut-up) pieces of paper into piles on a table. Or fill several envelopes with pieces of paper, and on each envelope, write the focused code. If you are using CAQDAS, it will be very easy to see and keep track of open codes, which are linked hierarchically to their parent focused codes. You can easily create, break links, or rearrange codes in CAQDAS. Whatever you choose probably depends on the size of your data collection—large studies cannot do without CAQDAS, but smaller-scale interview or focus group studies may use manual coding or coding in Word.

While it’s important in GT to pay attention to the most frequent codes, because these are the things that matter to informants, when you find a code appearing frequently it is also possible that you have unintentionally focused on something YOU deem important. Practice constant comparison by searching out one or more things that would be its opposite or contrasts.

At other times, there is an open code that is rare, yet sill meaningful. This can happen with in vivo codes, “where informants, after telling their stories, summarize the core message of their narrative with a pithy saying or memorable phrase” (p. 113), such as “cog in a machine”.

When you start focused coding, your memos will already be full of focused codes you can use (p. 113). How many focused codes should you have? Make a list of them: about 20 is ideal, and it is not advisable to go over 30 (p. 114). Once you have finalized your list of focused codes, stop open/descriptive coding and use these codes in future observations and interviews. If something new and seemingly important presents itself, shift back to open coding and try to integrate the new with the old stuff—but “do this as sparingly as possible. Your journey is not towards the creation of a unified theory of everything” (p. 115). There are many things you can study, but you are constructing a theory about a main phenomenon or basic social process. Of course there are an infinite number of other things that could be theorized if someone else were doing GT in the same research site at the same time.

Next, Hadley comes to axial codes. These explain “why people are engaging in certain activities, how these actions and activities start, when they change or finish, and in what way are they affected or influenced by other issues coded in your data” (p. 115). (I believe that the methodology I am trained in, linguistic ethnography, puts axial codes at the center, and there are frameworks such as Dell Hymes’ SPEAKING mnemonic for making the creation of axial codes easier.) Hadley explains that grounded theorists disagree on how useful axial codes are, and cites a couple scholars on either side of the debate (p. 116): some think they are essential for creating a good theory, and others think they overcomplicate the process. Hadley says “Valid points can be found on both sides of this argument” (p. 116), and personally, he thinks it’s best to do axial coding at the time when you do conceptual coding, which is Stage 3 of GT.

- Stage 1: Open/descriptive codes

- Stage 2: Focused codes or categories [Optional: axial codes]

- Stage 3: Conceptual codes [These are like axial codes]

- Stage 4: The theory

When you’re doing focused (and, if relevant, axial) coding, this is the time to consult relevant academic literature since you know what topics are frequently discussed and meaningful to your informants. Search academic library databases, ERIC, Google scholar, etc. by typing keywords collected from your qualitative data. An important point to note: “The success of this approach depends on whether the words and themes in your data match they keywords in online journals, or if you successfully hit on synonymous terms” (p. 116). Some conversations with senior colleagues or peers may be helpful here. Describe to them what you observe, and ask them what keywords come up in their minds that would align with the literature.

One great point Hadley makes about consulting the literature in GT is that “sometimes the most pertinent studies for informing your theory will be found outside the field of applied linguistics” (p. 116). When he did research on exhaustion, burnout, and disillusionment of EAP teachers, he found the same among qualitative studies of those in other “caring” professions like nursing. “Grounded theory is inherently interdisciplinary and encourages you to go wherever you need to find scholars who are discussing the issues that pertain to your investigation” (p. 117). Remember, though, that in GT you need to treat this scholarship on equal footing as the information from your informants.

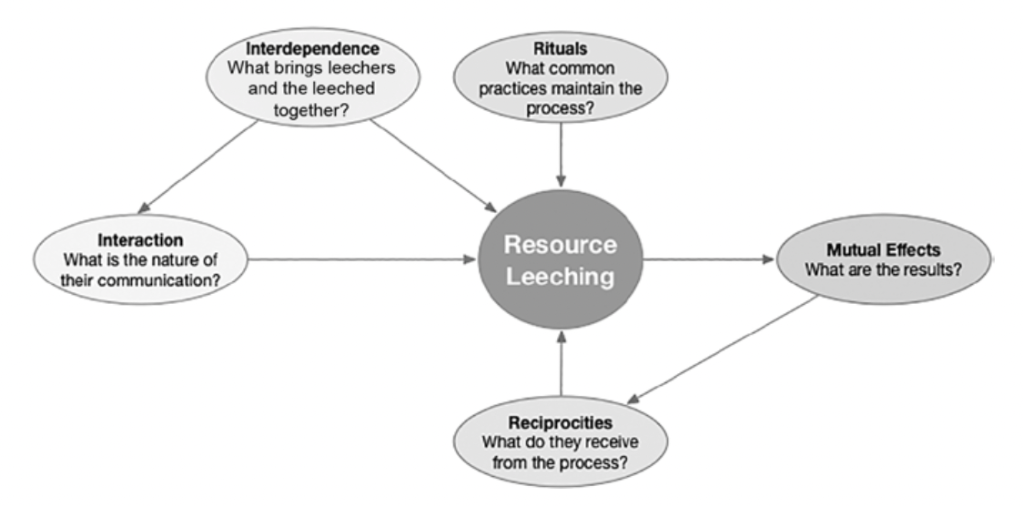

The next level up from focused and axial coding involves conceptual categories. Even though they are abstract, they should still “fit” and “work” with the empirical data (Gibson & Hartman, as cited in Hadley, p. 117). Conceptual categories may look much like focused codes, so here’s how I distinguish them from focused codes. Whereas focused codes are rather ordinary-sounding, conceptual categories are kind of catchy and draw you in. Hadley’s include: “flow management”, “bunker busting”, “resource leeching”, and “commando assessment” (p. 118).

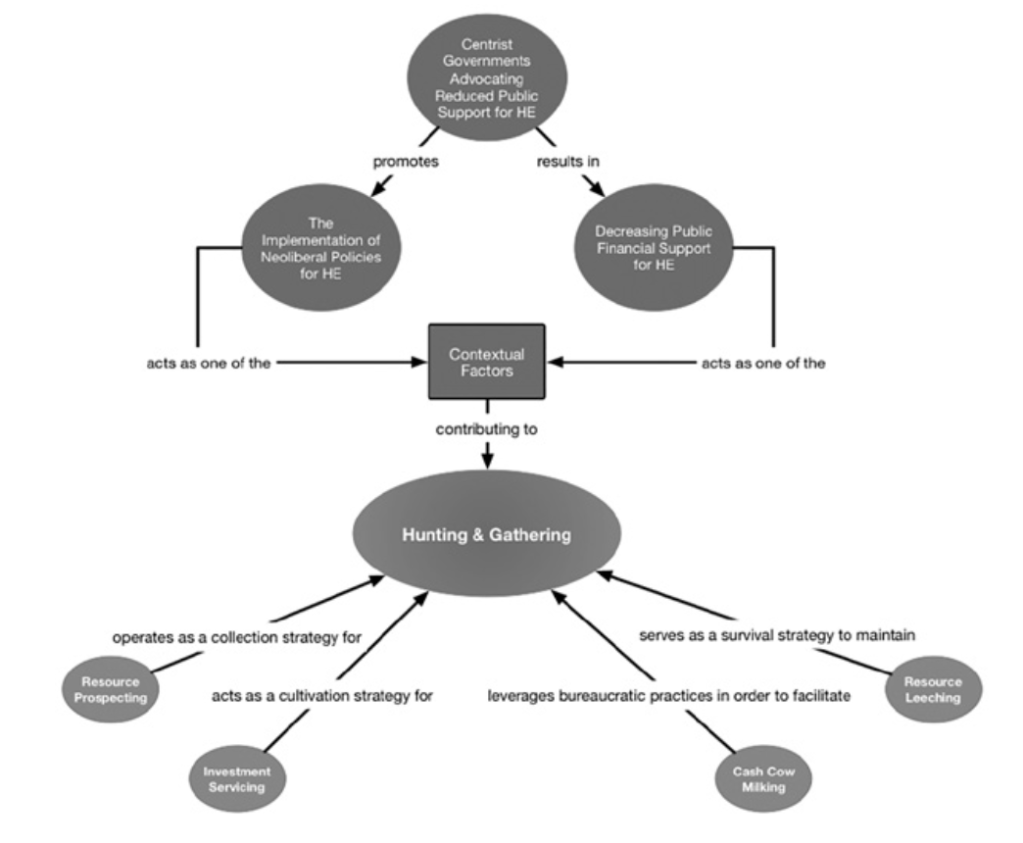

Some of these are likely to make people smile if they have relevant professional experience, as they will recognize the phenomena. Hadley writes: “Finding pithy expressions that aptly summarize groups of focused codes takes time” (p. 118). He recommends taking a notepad with you, since you never know when you will be visited by a conceptual category. Just as not all descriptive codes can be assigned to a focused code, not all focused and descriptive codes will fit within conceptual categories, so don’t feel everything has to be “sorted”. From 20-30 focused codes will ideally emerge about 5 conceptual categories that must be connected logically to one another in a flowchart outlining the theory/process:

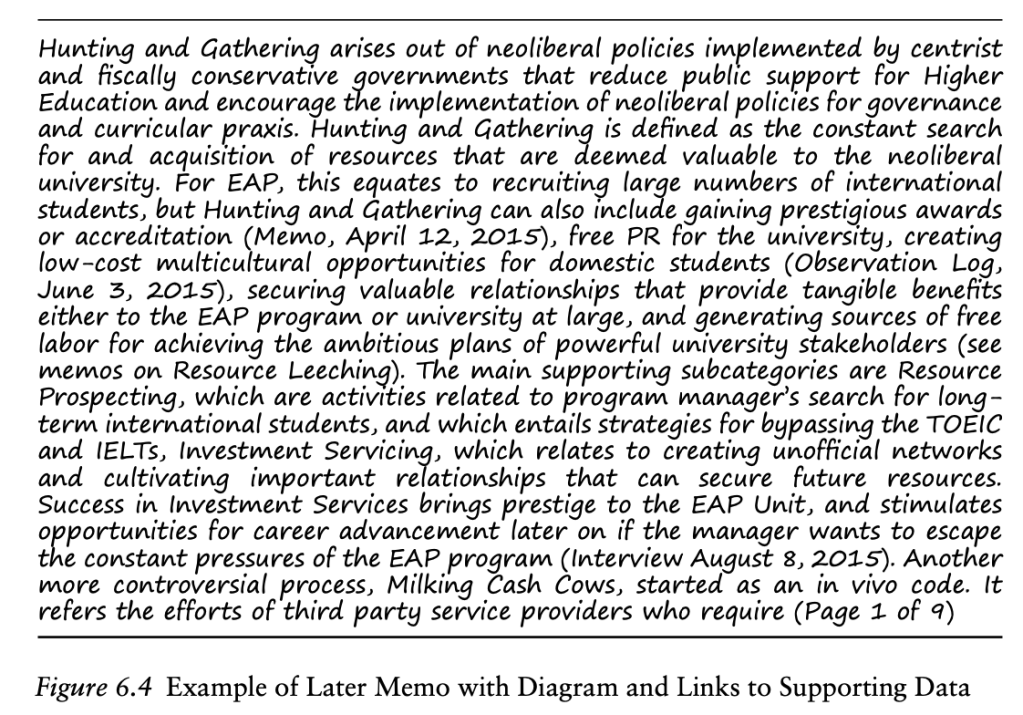

From my understanding, what the above diagram shows is the core category, the theory of “Hunting & Gathering” from Hadley’s own research (p. 126). The conceptual categories or things that surround it include “resource leeching” (see previous figure). There are other related ideas that come from the literature, which appear above “Hunting & Gathering.”

How did Hadley come up with “Huting & Gathering” as the theory? He says: “Start with studying the focused codes and supporting data to see if you can discern a trajectory of social action. Do some of the of the processes happen before others? Are there any that disrupt or change the situation? Do others happen after certain conditions have been met?” (p. 120). This is not just “data sorting” things into categories as in focused coding. It is something called “dimensionalization” (p. 120), which creates a flow chart like the one above. [Blogger’s note: Here is where people publish mediocre qualitative studies that are GT-esque, but all they do is present 3 or so themes that are just focused codes, with supporting evidence in the form of descriptive/open codes. That is not GT; that is the 5-paragraph essay expanded into a full-length journal article.] Conceptual categories have relationships to one another—they can function top-down, bottom-up, in a linear manner, or in parallel (p. 121). Each conceptual category represents a process. These processes can take place with “different levels of intensity or speed”, or they may be “mediated by social stratification” (p. 120). Hadley writes: “Your theorization on dimensions will be shaped by the discipline that you have undergone through coding, memoing, constantly comparing similar and conflicting cases, and interpretively linking much of this material to each other in order to move from description to higher levels of abstraction” (p. 121).

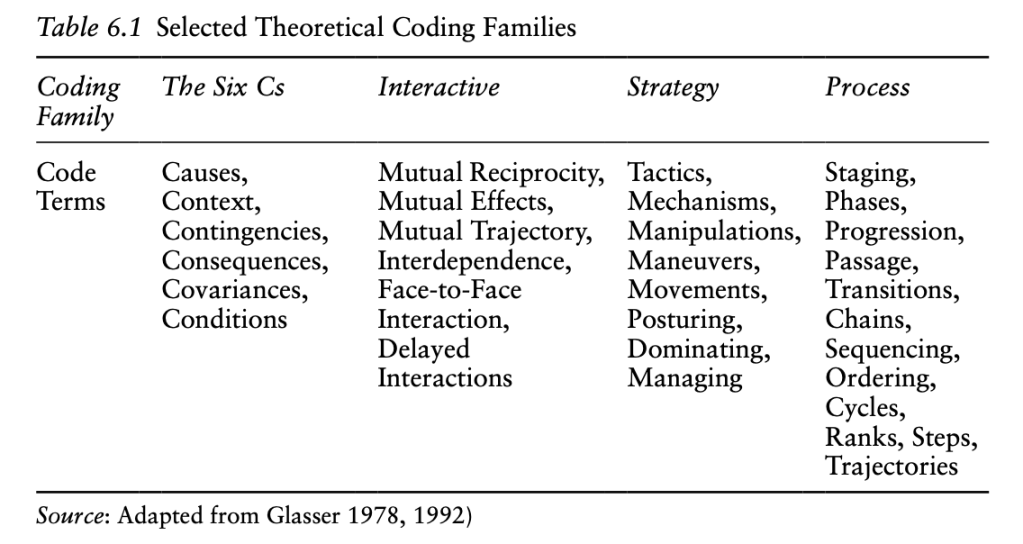

To give you some ideas about how linked conceptual categories form a theory that can be summarized in a flowchart, here’s a table (p. 122) of things you can look for in your data that Hadley adapts from Glaser (1978) and others:

Remember that the “proof” of these should be in the data, down to the descriptive codes. “In the instance of not knowing enough about one of these elements, along the lines of theoretical sampling, you will go back into the field to learn more” (p. 122).

When you’re doing theoretical coding, CAQDAS can arrange the codes for you around the conceptual categories. But it can also be done manually. The point is not what tool(s) you use, but to understand

the interactive association between these categories. What is the nature of their interaction? Which category affects the other and in what manner? Is the influence bidirectional, meaning that the categories orbit around each other, creating social tides that manifest themselves by periodic changes? … You should represent this interaction using verbs or action oriented phrases, such as ’stimulates’, ‘acts as a contingency for’, enables the transition to’, and so on. (p. 124; my bold)

There is no single right way to do this: “Diagrams are both internal and external representations” (p. 124) of both your mental process and what is really out there. Keep making note of where your theory needs more evidence and return to the field to fill in the blanks.

When it’s time to get to the core, the conclusion, the theory, explaining the basic social process, you should be able to do this in one grand memo like this:

Focused codes with lots of links and “outward flow” (p. 127) will tend to rise up as the conceptual categories. Find ways to connect them, and then keep finding examples in the field (theoretical sampling) and searching the scholarly literature for these concepts that you have created.

Hadley ends this chapter with a discussion of when you know you have “enough data.” This is called reaching theoretical sufficiency/theoretical saturation. It is when collecting more data is not adding more to your understanding of a phenomenon. Note the singular here: “a phenomenon.” You could always collect more data pointing to other phenomena in the research site, unto infinity. But collecting more data isn’t going to add more to your understanding of the particular phenomenon and its conceptual categories. For example, Hadley believes that interviewing 100 people tends to be unnecessary to investigate a phenomenon; the theory emerges after about 30-40 interviews (p. 130), provided that you have sampled widely enough and are focused on that phenomenon.

In sum, constructing a grounded theory (Corbin & Strauss, as cited in Hadley, 2015, p. 130) is like constructing a pyramid of evidence in which concepts are supported by earlier concepts. Open/descriptive coding is the first level, until patterns emerge (focused coding). Constant comparison helps to identify the patterns and outliers. At this point you consult scholarly literature for further insight on the topics that have emerged from the ground. Axial codes may also be created. Then, conceptual categories are formed that show the dimensions of a social process using arrows and active verbs and verb phrases. Lastly, “a core category, main concern, or overarching phenomenon that has the most influence over the interplay between the categories, is then raised up as the touchstone for the entire theory” (p. 130). You can continue to study this main concern—for some, the answer to the question “What is your dissertation about?”—through further investigation of its dimensions (conceptual categories), and more field research, until you are satisfied that you have reached theoretical sufficiency, or you run out of time allotted for doing the research. Hadley calls memo-writing the “lifeblood” (p. 132) for theory creation, as memos at different levels connect the codes at each level.

Chapter 7: Writing up GT

Many books on a methodology end with chapters on how to write papers using that methodology (genre conventions), and this book is no exception. In the first part of this chapter, Hadley discusses how to write a “good” GT paper. In the second part, he gives you suggestions to effectively answer criticisms of a GT study (e.g., from a thesis committee member or peer reviewer).

How to write a GT study

- When you try to publish a GT study, it is commonsense to send it to a journal that is open to qualitative methodologies. Also, when deciding how much data to put in the article—that is, many articles/books can be published from the same study—consider “conceptual capacity load” (p. 133), which means there is only so much data a piece can accommodate. Then ask: Which higher conceptual categories (findings) will be of MOST interest to the audience of that piece? Consider the practical implications and take-home message of those findings: “This will make it more likely that your target audience will retain and apply parts of your grounded theory to their lives” (p. 135).

- As much as you have word space for, clearly present your methodology. At least, write enough to show that you understand GT and haven’t just cited Glaser and Strauss or Strauss and Corbin, and that you have followed the core procedures of GT, which are discussed in this previous post. State and justify procedural decisions, sampling methods, problems or challenges and what you did about them, and your theoretical paradigm (see previous post).

- Then there’s the findings section. All GT studies have quotes from informants, but if your quotes are too long or too many your readers won’t know what they’re looking at or why they’re looking at it (not enough analysis). However, quote too little and people will say, “Where’s the data?” Balance quotes with analysis.

- The literature review will present published works you found during later stages of coding (focused and theoretical coding) rather than the start of the study. You should also present any background information about the contexts and causes of the social phenomenon you are studying, such as census data, press releases, hard facts from news sources, etc.

- While it may be a Western convention, Hadley recommends summarizing your whole theory upfront—What is the social phenomenon you are studying and what are its components?—and then go into detail about each of those components, to the extent permitted by the word limit (p. 138). This is a “top down” or deductive presentation of information. I think this is his personal preference, but it is a writing convention from the early days of GT. [Blogger’s note: I prefer those qualitative researchers who give you just enough in the abstract to know the study is worth reading, such as the core concept or category, but don’t reveal all until you’ve read the entire study, such as Julia Menard-Warwick and Deb Palmer. Otherwise, the study gets rather dry and I get impatient going through it since I know everything from the beginning. There is no novel-like revelation or “uplift” gained during the climax/ending].

- An important thing to include would be a flow chart showing the theory, which is fundamentally a social process, as this helps the reader visualize it in a nutshell. “Supported by interview extracts and other scholarly citations, these will add clarity and persuasive power to your argument” (p. 138). [Blogger’s note: Such a flow chart looks great on a PPT slide at a conference! But don’t hack it, please don’t hack it.]

- Another thing that makes your paper engaging and readable will be the narrative approach used by Strauss and Corbin, with interviews, photos, and other forms of data that draw laypeople in.

- You should avoid using too many new theoretical terms, which will not only overload readers already trying to make sense of your theory and data but may also make you look like you’re trying to sell them something commonsense couched in fancy language (p. 141).

How to answer criticisms of your GT study

I will not go over every common criticism of GT studies mentioned by Hadley in this chapter (e.g., “Can you replicate your study?”) as such questions will not often be asked of you these days now that qualitative research is well established, unless you are dealing with people not familiar with it. Instead, I will focus on questions/criticisms that other qualitative researchers may still have.

- “I don’t see how your theoretical concepts emerge from your data.” In my (the blogger’s) view, if this happens, the audience member or thesis committee member might be right. Hadley points out that it could be the questioner’s background differing from your own—they may not be seeing what you see (p. 145). In my opinion, if the data does relate to your theoretical concepts and you’re not shoehorning it to fit, this is usually just a minor writing problem or PPT design problem: there is too much quoting/description and it needs trimming down and replacing with more of your written analysis. Or there is a lack of signposting (explicit transitions to make connections between ideas).

- “Your theory is wrong; I have a contrasting example.” As you know from reading about GT so far: “Instead of satisfying his urge to ‘put down’ a colleague, he would have realized that he has merely posed another comparative datum for generating another theoretical property or category [i.e. an exception]… Nothing is disproved or debunked.” (Glaser and Strauss, as cited in Hadley, 2015, p. 145)

- “What have you done to validate your study?” Like quantitative researchers, qualitative researchers care about study validity. Glaser believed that constant comparison is the key to validation, while other grounded theorists have posed criteria for “what makes a qualitative study good” apart from the 2-3 main ones in quantitative research: validity, reliability, generalizability. Hadley likes the criteria proposed by Charmaz (p. 146):

Hadley says he likes Charmaz’ framework because in the end, GT should challenge traditional power structures in academia, in that the end users of the theory (the informants) “are the final arbiters of its quality” (p. 147).

4. When someone says your theory is obvious. Hadley believes this can happen in a professional field when both the researcher and the questioner (e.g., education professionals) think something is obvious, but it is not obvious to laypeople (p. 147). He would say that the critic, also an insider, would just be validating your theory. But I think researchers should uncover things that are not immediately obvious to anyone, insider or outsider.

Hadley suggests having extra slides at the end of your PPT to deal with criticisms that you anticipate. Particularly after you have been asked a hard question you weren’t 100% prepared for, the next time you give the presentation, he recommends adding an explanatory slide or two to the end of your presentation so it doesn’t happen again (p. 148). This is not just to defend yourself against jerks, but to improve your presentation; Hadley says he does it “when I encounter a new question that warrants a clear and thoughtful answer” (p. 148).

This chapter concludes with a great quote about research that is not positivist. Hadley says that when you are operating from a positivist paradigm, researchers are “equal” before certain rules governing study validity. When you operate from a non-positivist paradigm, there are no more universal rules and you have to rely on interpersonal faith and trust:

The propensity is towards seeing diversity of thought as something that is not only helpful, but something that should be celebrated. In the absence of this trust and mutual appreciation, the situation quickly descends into one where the person having the most power can dominate discourse to the point that their paradigms, interpretations, and evaluations, all reign supreme. In effect, if bereft of humanity, pattern [interpretivism] and process [social constructivism] yield to tyranny—either from without or from within any particular scholarly discourse community. (p. 149)

This is why he says you should pick your thesis examination committee carefully when doing a non-positivist study (p. 149), which does not have universal ground rules as to what is (in)valid methodologically. Whether a person is hostile to qualitative, non-positivist research (“tyranny from without/outside”) or they are a qualitative, non-positivist researcher who will manipulate your data in favor of their own theory (“tyranny from within”), it’s not going to be fun for you.

Chapter 8: Summary

In Hadley’s brief conclusion, he says you should have gotten the following things from the book. First, you should know more which approach to GT you want to take: Glaser’s, Strauss’, Charmaz’, Clarke’s… so you can read more about it. Second, this book should have gotten you thinking about the logistics of your project and the skills and dispositions needed to carry out such a project. Importantly, you should be familiar with the basics of coding: first, open and descriptive, going back and forth with memo-writing, looking for patterns that frequently emerge and constantly comparing it with any exceptions or outliers. At the next level, you group similar things together (focused codes), try to find the connections and causal relationships between them (axial and conceptual codes), and then “onward to theorization” (p. 153).

The idea that you should not consult the scholarly literature in GT is a myth—you simply need to put it in its place. Consult relevant literature based on what is emerging in the theory during focused coding, not prior to going out in the field. Also, treat the scholarly literature as just another informant, or even as a lesser informant since it is not primary data.

Finally, when presenting/writing up GT, remember that

A grounded theory is not a collection of descriptive themes, but instead an interconnected set of social processes, each related interactively, around a main concern or overarching phenomenon. Because of the depth of detail that you have within your collected data, memos, and other materials, generated as they have been from the rigors of GT, you have developed an awareness as to how to present your theory. (p. 153)

If you are reviewing a paper that says it uses GT, it should not be a list of (often 3) themes that the researchers say “emerged” from the data. You want to see a flowchart of interconnected social processes with some empirical data to back them up. Plus, what the authors are presenting should represent the most prevalent codes across the data (what is the evidence that they were prevalent?). The authors should also discuss exceptions, and their methodological narrative should outline what literature they consulted and when—so you can see that the literature was consulted at the focused coding stage or later. As stated earlier, literature from other disciplines is welcome as it may have practical relevance. One of the cool things about GT is that research from another field, if it is related, is more welcome to connect the findings to than research from within the field if it is not what is shown to be relevant to the data gathered “on the ground.”

All this is hard! “Grounded theory… starts within the social arena and works its way up” (p. 155). It is important work for “revealing to others what has always been there, but which has remained unseen because until then, people lacked the words. Once we can, in theoretical terms, name something that is taking place in our educational environments, we can then do something about it” (p. 155).

References

Anthony, L. (2014). AntConc (Version 3.4.4) [Computer Software.]

Waseda University. http://www.laurenceanthony.net/

software/antconc/

Glaser, B. G. (1978). Theoretical sensitivity. Sociology Press.

Holstein, J. A., & Gubrium, J. F. (1995). The active interview. Sage.

Sieber, J. (1992). Planning ethically responsible research. Sage.

2 thoughts on “Grounded Theory in Applied Linguistics Research: A Practical Guide (part 2 of 2)”

Comments are closed.