If you’ve ever done coding in qualitative research, it’s important to know where that process comes from: an influential methodology called Grounded Theory (GT). GT became so popular in the late 20th century that its coding process was adopted into other qualitative methodologies like case studies, action research, phenomenology, and ethnography. The central premise of GT is that theories must be generated from the ground up, from the data and informants, rather than the preconceived interests and biases of the researcher. In this post, I summarize a textbook on GT in applied linguistics by Prof. Gregory Hadley at Niigata University. It’s only 200 pages, engaging, and accessible—covering what you need to know about the epistemology and history of GT (and qualitative research in general), in addition to providing a practical guide on how to do GT.

Hadley, G. (2017). Grounded theory in applied linguistics research: A practical guide. Routledge.

This is the first of a 2-part series of posts, following the book’s 2-part structure. In this post, I summarize the first 40% of Hadley’s book, which is about the epistemology and background history of Grounded Theory (GT). The other 60% of the book is on how to do GT, which will be in my next post.

Introduction: Where did Grounded Theory originate, and why?

Until the 1960s, social scientists conducted research in the same way as scientists in chemistry and physics: through statistical analyses and experimental designs. To conduct social sciences research involving non-numerical data (such as interviews, field observations, and other “soft” data) was seen as unscientific, subjective, and biased.

But by the 1960s, social scientists began to explore alternative types of methods. One of the most successful endeavors was Glaser and Strauss’ (1967) The Discovery of Grounded Theory. It exploded in popularity in just two decades across the social sciences, especially in the “helping professions” like teaching, social work, and nursing, and remains popular today (citation count: 171,000+). In 2000, Titscher et al. (2000) estimated that nearly 2/3 of qualitative research in the social sciences employs GT fully or partially—especially its common element of “coding” or finding key themes in (often verbal) qualitative data.

There are quite a few misconceptions about GT, despite how many claim to use it. Hadley describes some of these (p. 7): “Some have heard that it does not require any reading of the scholarly literature and that the methodology entails the simple task of going out into the field in order to discover common themes happening among a particular group of people.” He also points out that some students “end up writing something that sounds suspiciously like what they believed before starting the project” (p. 7), which is contrary to the key principles of the method—to build the theory from the ground up rather than impose a worldview on it. Hadley highlights that GT requires institutional resources and support, as well as the right temperament, time, endurance, previous knowledge about issues in one’s discipline, and experience with field research (p. 9). In addition, GT requires pragmatic flexibility, in that one should “see the methodological discussions in this book less as hard-and-fast rules and more as tools that you should adapt for the needs of your particular grounded theory project” (p. 11).

In his book, part 1 of 2 deals with the history of grounded theory, first explaining what different paradigms in the social sciences are (Chap. 1), then discussing how the original 1960s GT (Chap. 2) and modern versions of GT (Chap. 3) look different.

Chapter 1: On paradigms

A paradigm is a belief about the nature of reality combined with assumptions about how to conduct research. There are 3 main paradigms in Western social sciences research, which have different names, but which Hadley calls:

- paradigms of structure (mainly positivism)

- paradigms of pattern (such as interpretivism, phenomenology, humanism… among others)

- paradigms of process (such as deconstructivism, post-modernism, poststructuralism… among others)

I think this part gets a little complex, so I will give my own explanation. I call the 3 paradigms (1) positivism, (2) interpretivism, and (3) social constructivism, and will copy/paste what I have in another blog post called “Know your epistemology”:

- Positivism posits that we get to the objective “truth” or “facts” behind a social phenomenon. For example, in a fifth grade class, Leon says he was bullied by Zack. If we are to take a positivist approach, we examine the truth behind Leon’s claim: whether or not (or to what extent) he was indeed bullied by Zack. When it comes to language learning, for example the research question, “To what extent, and for what reasons, are students in Hong Kong (a Cantonese-speaking society) motivated to learn Mandarin Chinese?” we likewise would be attempting to get the “facts.”

- Interpretivism and social constructivism are alternative epistemologies to traditional positivism. (I do not mean to say that positivism is outdated; it is simply the default epistemology.) Interpretivism (I think some people call it “subjectivism”) seeks to explore what people think is the fact of the matter, not the actual fact of the matter. What does Leon think about the situation? How about Zack? How are their perceptions influenced by various personal factors? Why do students in Hong Kong think they want to learn Mandarin Chinese? How do they see themselves as ‘motivated’ Mandarin learners? (We are not attempting to capture their actual motivation to learn Mandarin, but their perception of their motivation.)

- Social constructivism, the research epistemology I principally am trained in, is conceptually the trickiest. It is not about the facts, or what people think to be the facts, but what they collectively agree on (openly pretend) are the facts. What they socially construct to be facts. We would thus examine how Leon, Zack, their classmates, and their teacher negotiate the story of what happened. Or, we would examine how Hong Kong students perform being “motivated learners of Mandarin” (in their words, actions, self-portrayals in conversation and on social media)—not whether they are actually motivated learners of Mandarin, or whether they actually believe themselves to be motivated learners of Mandarin. Because it is social, social constructivist research also examines how others respond to performances (with acceptance, doubt, challenges, similar/different performances, etc.).

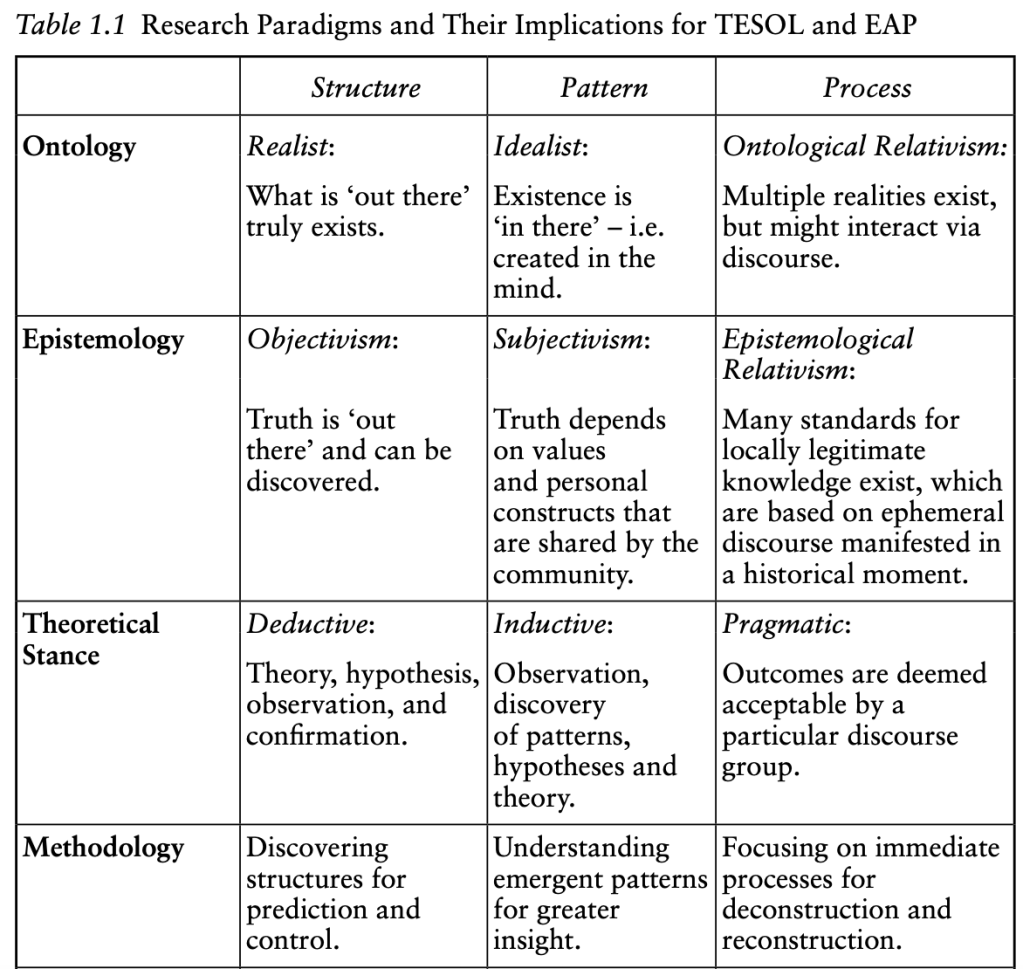

Here’s how Hadley maps out the 3 paradigms in the social sciences (p. 23):

In a positivist view, you have the real truth/facts to discover. This is the view that is associated with traditional, quantitative, experimental and statistics-driven research like STEM research. In the interpretivist view, you seek to discover what are people’s subjective viewpoints, individual (or group). In the social constructivist view, what you study is the process by which people come to agree on contingent versions of reality. Hence, paradigms of structure (i.e., the structure of reality, in positivism), paradigms of pattern (what are the common patterns in individuals’/groups’ thinking?), and paradigms of process (how do we agree on what is real).

Hadley doesn’t have any opinion on what is a “best” paradigm or approach to social sciences research. He says they all have their place, in that paradigms of process show us how people come to their belief patterns, and that is their reality: the structure of their existence (Lowe et al., as cited in Hadley, p. 24). An important thing to note is that even when people are using the same methods (e.g., interviews, observations in qualitative research), they can be operating from different paradigms (p. 17). For example, you can examine narratives for information as to what is real truth/fact—the same way news reporters do. Hence, narratives can be positivist data if you develop a structured coding scheme (i.e., rubric/instructions for analyzing the data) and test for interrater reliability (i.e., have two or three colleagues code the same data set, or a sample of it, and see if they come up with the same key points, measuring their percentage of agreement). Narratives can also be analyzed for how people construct what really happened in oral conversation (social constructivism); this approach is called “narrative analysis.” And narratives in interviews can provide a window into individuals’ subjective understandings of events (interpretivism); this approach is called “narrative inquiry.”

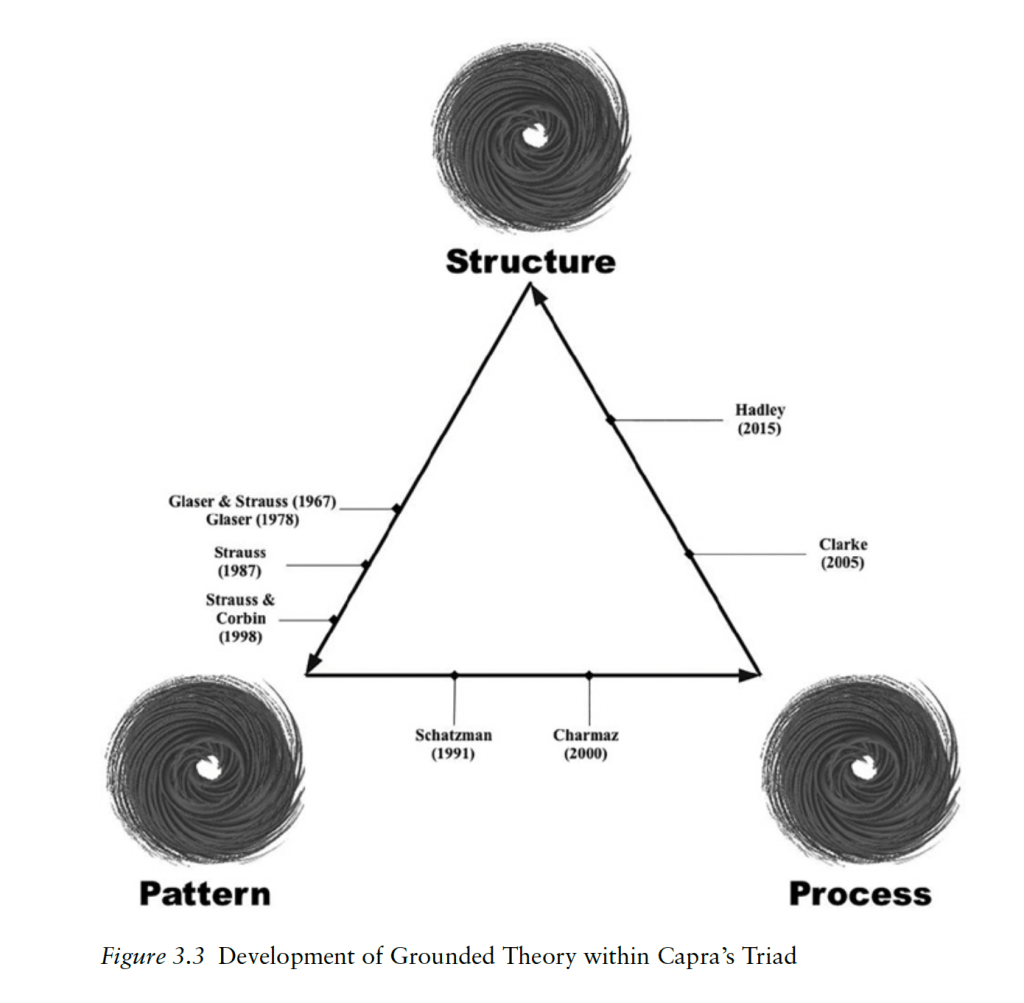

You might then ask which paradigm Grounded Theory falls under. In fact, different versions of GT across time have adopted different paradigms, and this is what Hadley comes to next.

Chapter 2: Origins of Grounded Theory

The Birth of Grounded Theory

Grounded Theory originated in the 1960s with the research partners Glaser and Strauss, a pair of sociologists at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF).

Strauss was a professor at UCSF who recruited a number of scholars to work with him, including Barney Glaser. They ended up working on a project with terminally ill, elderly hospital patients, and wrote a book called Awareness of Dying (1965) about “what happens when the hospital patient begins the trajectory towards eventual death” (p. 30), This was not a methodological book but a book about dying, and it contained the first application of GT. Two years later, Glaser and Strauss published The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research (republished 1999 and as an ebook in 2017), which was a book about how they did research for Awareness of Dying. Yet The Discovery of Grounded Theory was still a theoretical work, not a “how to” book. You can catch people who only have a superficial understanding of GT if they cite Glaser and Strauss (1967) as if it were a manual; it is likely they never opened it. A more methodological guide would be Strauss and Corbin’s Basics of Qualitative Research Techniques (1998), cited 67,000+ times.

Here are some basic premises of GT that have never changed:

- GT seeks to do research in “an open-ended, exploratory manner” at first, and then “becomes more specific as the research progresses” (p. 31). What this means is that you must patiently collect a ton of information about everything at a research site, and only after certain problems, themes, or processes have emerged in the data, then you start following leads—interviewing more specific people and collecting select documents and data to shed further light on the emerging issues (this is called “theoretical sampling” to develop the theory as it emerges).

- At the onset, the researcher must enter the research setting with as few pre-determined ideas as possible. The goal is to avoid developing a confirmation bias, based on either his/her/their own ideas or from the perspective of earlier studies, and “to remain open to what is actually happening” (Glaser, as cited in Hadley, p. 2017). Only later do you start accessing the scholarly literature with issues or problems discussed by informants. While different famous GT researchers have disagreed on when existing research/literature should be consulted, such academic research should not be privileged but treated as just another body of informants (p 35).

- Data collection and analyses happen at the same time, in contrast to experimental studies, and findings that contradict regular patterns are especially noteworthy, since they define the limitations of the pattern and lead to a richer picture of what is going on. This need to pay attention to and report the contrast between the general/typical pattern and the exception(s) is called the “constant comparative method”, another central aspect of GT that has always been part of the method.

- After “multiple loops of data collection, coding, and memoing until the researcher finds that very little new information or additional properties are forthcoming” (p. 36), grounded theorists reach what they call “theoretical saturation” and they start to make connections between the codes, generating the theory from the ground up. The theory should be based on the categories and codes that contain “the largest amount of supporting data, memos, properties, and social interactions” (p. 36), but also must note the exceptions.

All these points—(1) the open-ended and exhaustive collection of data at the beginning (waiting patiently and “fishing” rather than “hunting” for a theory), (2) the need to demonstrate that the theory is mostly tied to the informants’ data by de-privileging academic research, and (3) the need to write up the report based on what was most commonly found, along with the requirement to note exceptions—are meant to guard against non-rigorous, cherrypicking, self-interested, and/or hasty-to-publish ways of doing qualitative research that are disconnected from the lived realities of participants.

The Conflict between Glaser and Strauss

In the 1990s, Glaser and Strauss had a major falling out, which I believe had to do with the different venues in which they ended up working. Strauss was tenured at UCSF and continued to work in academia, but Glaser was passed over for tenure and started his own publishing company (Sociology Press) and his own GT institute.

As GT grew in popularity in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s, it was clear that few were using it in the rigorous way described by Glaser and Strauss. Benoliel (1996) found that many were neglecting key practices like writing memos immediately after observations and interview encounters, engaging in constant comparison of the trend and exceptions, conducting theoretical sampling (i.e., you sample based on the emerging theory, which you must be able to articulate), and using theoretical coding in a systematic, multi-step, well-defined process. Besides a cursory in-text citation to Glaser and Strauss (1967), Benoliel found that there was little evidence that GT was being used as all in many studies. Therefore, Glaser and Strauss set out, each on his own, to restore GT to methodological rigor.

Glaser was firm on researchers avoiding ANY literature before entering the field until the theoretical sampling stage (with the exception of history and archival documents, which are part of “real world” data and not academic literature). This is because he focused passionately on theory generation rather than theory verification—independent of the requirements of grant funders, scholarly circles, etc.

In contrast, Strauss, who continued to work in academia, went on to develop complex coding schemes with his new research partner, Juliet Corbin. Glaser (and others) found these coding schemes too complicated. Strauss and Corbin encouraged researchers to do a literature review before going into the field (I agree with them on this point) because it “heightens theoretical sensitivity and strengthens the potential of generating new ideas and insights” (p. 40). And yet, because of the way academic publications are monitored based on textual information, they also developed a very demanding coding style, not only involving full transcripts of interviews but an insistence that researchers examine “each line of transcribed interviews… sometimes studying each word” (p. 41).

Strauss and Corbin also came up with something called “axial coding.” In Glaser and Strauss’ original GT, you come up with the initial codes first, then start clustering them into broader categories, and then come up with the theory. Strauss and Corbin’s axial coding is an intermediate step where the first codes are further investigated with “causal conditions, intervening conditions, context, action strategies, and consequences” (p. 41). (Blogger’s note: An axel is the central part of a wagon that ties the parts together; this is where the name “axial coding” comes from.) Other GT theorists do not do axial coding, but all GT involves different levels of codes, typically (1) open coding at first (anything you notice that could be of value), then (2) the intermediary codes like axial coding, or (what is more common) focused codes or categories of initial codes, and finally (3) selective codes (to test your emerging theory). Names may differ across manuals, but there are these general steps. In the end, you ideally have an “‘explanatory theoretical framework’ which is often accompanied by a diagrammatic representation of the trajectory of causes, consequences and changes taking place in the phenomenon” (Strauss & Corbin, as cited in Hadley, p. 42)—in other words, something like a process flowchart.

[A note on writing style: while Glaser’s scholarship is terse and to the point, Strauss and Corbin write in a style more familiar to qualitative researchers—in a narrative form, and fairly accessible to laypeople, following a group of sociologists called the Chicago School. Their works are “replete with quotes from the informants that serve both to enhance the richness of description and demonstrate that the concepts have been generated from the data” (p. 43), and this is the style that most qualitative researchers adopt, in my experience.]

So why did Glaser and Strauss get into a bitter conflict rather than simply go about practicing things somewhat differently? Glaser reacted negatively to Strauss and Corbin’s work, criticizing their (1) not letting the theory emerge just from the data, because they allowed the researcher to consult the literature, and (2) complex coding scheme. While Strauss did not really respond to Glaser that much, he and Corbin argued that “a child once launched is very much subject to a combination of its origins and the evolving contingencies of life. Can it be otherwise with a methodology?” (as cited in Hadley, 2017, p. 44). In the 1990s, a large body of literature emerged as different members of the GT family took different sides of the conflict, while researchers outside the family criticized GT for terminological confusion and overcomplicated methods.

However, the next generation of grounded theorists recognized, similar to Glaser and Strauss in their more temperate days (when they were working together), that

No sociologist can probably erase from his mind all the theory he knows before he begins his research. Indeed the trick is to line up what one takes as theoretically possible with what one is finding in the field. Such existing sources of insight are to be cultivated though not at the expense of insights generated by the qualitative research, which are still closer to the data. A combination of both is definitely desirable. (Glaser & Strauss, 1967/1999, as cited in Hadley, 2017, p. 45)

A more serious concern than the extent to which one should consult the published literature, Hadley notes, is an uncritical attitude towards the collected “raw” data as if that was the authoritative truth (i.e., Glaser and Strauss were both positivist in their approach to GT). The problem with this approach, Hadley explains, is as follows:

suppose that during the Second World War, a grounded theorist, who was a member of the Nazi Party, sought to discover the basic social process of the transportation office under the administration of Adolf Eichmann. It would be very likely that, based on the interview data and observations of daily issues in the office, the main problems and processes to emerge from the informants would be notions such as ‘keeping the trains on time’ and ‘negotiating transportation stoppages’. This would completely miss the broader issue—that of millions of Jews being carried off to be exterminated in concentration camps. (p. 46)

Therefore, more contemporary grounded theorists began to explore (1) the subjectivity of the researcher and participants and (2) the potential of grounded theory to address issues of social justice. These mirror other developments in applied linguistics, such as the Sociocultural or Social Constructivist Turn in the late 20th century and the Critical Turn of the early 21st century.

Chapter 3: Contemporary Grounded Theory

In this chapter, Hadley talks about several versions of contemporary GT—as well as how GT is different from other qualitative methodologies like case studies, action research, phenomenology, and ethnography.

Schatzman’s Dimensional Analysis (Schatzman, 1991)

A former student of Strauss, Schatzman sought to simplify Strauss and Corbin’s complicated coding scheme and bring it over to “the natural instincts that people have for studying sociological problems” (p. 49). According to Schatzman (and I agree with him!) all people are “incipient scientists testing out their theories of the world through personal empirical experiences” (p. 49).

Schatzman’s focus was the dimensionality of social phenomena, which many of us can relate to. For example, just as an object has a color, size, and weight, a relationship might have a degree of “durability” or “openness”, and an idea might have a level of “popularity” or “simplicity” (p. 49). These are dimensions of the phenomenon being investigated. To investigate a dimension of a phenomenon (e.g., “the durability of relationships”), differing perspectives of many informants are sought, and “these multiple voices are constantly compared until they combine into interesting patterns identified by the researcher” (p. 50). Researchers should analyze contexts and conditions under which the phenomenon take place, the processes or actions people use to deal with certain issues, and finally the consequences of what happens (p. 50). Schatzman influenced many students at the University of California for nearly 30 years without calling much attention to himself, and Hadley calls it “regrettable” (p. 50) that he waited until 1991 to publicly introduce dimensional analysis. In addition to critiquing Glaser’s excessive focus on inductive theorizing in the field only (that is, Schatzman thought it was useful to consult the literature), and revising Strauss and Corbin’s inaccessible approaches to coding, Schatzman added a subjective awareness to GT—in which the researcher recognizes themselves as an inevitably subjective individual in the data collection and analysis process. He therefore recommended a detailed but reader-friendly account of the research process in which the researcher explicates what they did and what role their subjectivity played.

Constructivist grounded theory (Charmaz, 2006)

Kathy Charmaz, a student of both Glaser and Strauss, added a social constructivist angle to grounded theory (Charmaz, 2006) by studying “interplay existing between the worldviews of the researcher and informants” (p. 50). Not believing that objectivism was possible, Charmaz, like Schatzman, felt that GT was an “interpretive theoretical practice”, not “a blueprint for theoretical products” (as cited in Hadley, 2017, p. 51).

Charmaz also adopted a simpler coding scheme than Strauss and Corbin, with an open coding stage followed by a secondary coding stage that collapsed similar codes into categorial labels, followed by theoretical coding. Similar to all grounded theorists, she advocates the use of memos, more focused theoretical sampling (i.e., the data search becomes narrower and informants are more selectively sought out) once the theory begins to emerge, and constant comparison between typical patterns and outliers. She also aimed to achieve a fair balance between the views of informants and researcher, believing, in contrast to Glaser and Strauss, that the theory takes form in the mind of the researcher rather than being discovered in some external reality:

Neither data nor theories are discovered. Rather, we are part of the world we study and the data we collect. We construct grounded theories through our past and present interactions with people, perspectives, and research practices. (Charmaz, as cited in Hadley, 2017, p. 51)

In other words, researchers are informants just like participants are, and their presence in the field changes the environment and hence the data. This is inevitable—and something that social scientists started to accept as not necessarily problematic as qualitative research matured in the late 20th century.

Situational analysis (Clarke, 2005)

Adele Clarke, another student of Strauss, was influenced by a general school of thought that affected Western humanities and social sciences research in the late 20th century, called “postmodernism.” This is roughly equatable to the paradigm of social constructivism, and her approach to grounded theory is known as “situational analysis.” Any “truth” is thus a snapshot of the constant mix of multiple perspectives, as the “truth” is constantly negotiated and renegotiated. (Some people call this way of thinking “relativism”, i.e., the facts are relative; depends whom you ask.) This postmodern grounded theory (Clarke, 2005)—which Glaser would probably have disapproved of—is similar to Charmaz’ take, in which the process of theorizing is prioritized over theory as a product.

[Blogger’s note: While Hadley doesn’t criticize postmodern GT, he spends such little time on it that I suspect he isn’t a big fan of it, because of his own take: critical GT. The critical education scholar Paolo Freire rejected relativism, in that we should not abandon a search for truth, because that is related to social justice.]

Critical GT (Hadley, 2015)

Remember Hadley’s example of why a positivist GT would not work if GT existed during WWII and someone were trying to use it to study Nazi Germany. To address “issues related to power, inequality, gender, and justice” (p. 53), among others, we would need to be able to state more objective facts about the inequitable distribution of resources or discriminatory practices, or genocide. Certain interpretations would be unacceptable—such as the view that the situation is positive, or that the discrimination or genocide doesn’t/didn’t happen. Hadley, for example, used critical GT to discuss problems of domination, inequality, exploitation, and professional colonization in English for Academic Purposes units in the US, UK, and Japan (Hadley, 2015). This kind of theory seeks some degree of objective truth because it needs to yield actionable next steps, unlike the original approaches to GT, which largely sought to understand social phenomena.

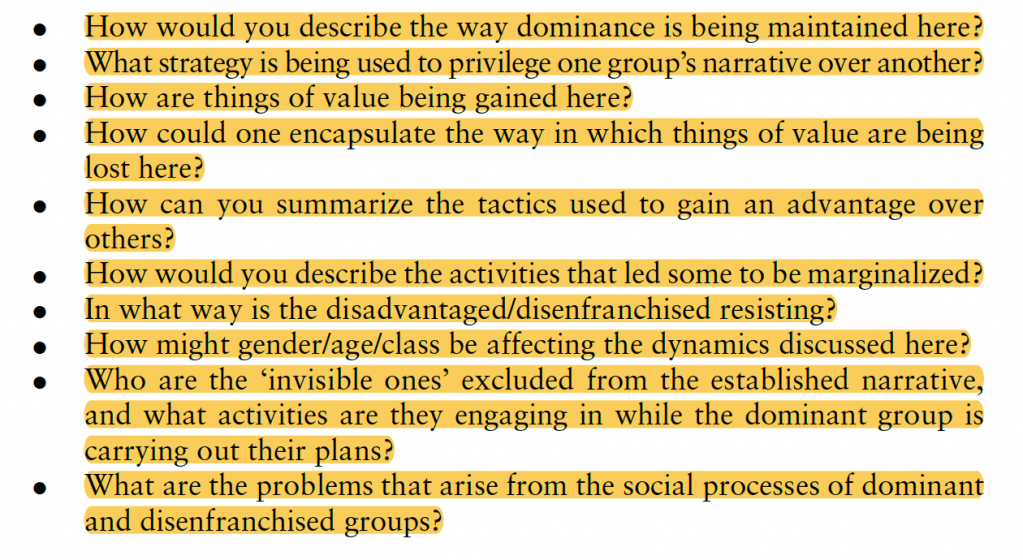

Moreover, unlike the original GT, critical GT does not only focus on the informants, but contextualizes the theory in its broader historical, cultural, or economic milieu, as related to local, national, or international politics. (The difference between Glaserian and critical GT is actually similar to the difference between Conversational Analysis and Interactional Sociolinguistics—and there are possibly other examples of types of research that use the same methodological tools but have “apolitical” versus “political” lenses.) Unlike Strauss and Corbin, Hadley thinks it’s enough to do open, focused, and theoretical coding without axial coding. Beyond asking the question all GT researchers ask, “What is going on here?”, in critical GT, the researcher asks, “Why is this going on?” (p. 54; my italics). Hadley believes that theoretical coding can be guided by the following questions:

In writing up critical GT, Hadley believes in presenting it similar to the way Strauss and Corbin and the Chicago school sociologists did—in narrative form, accessible to laypeople, with quotes of research informants and empirical data collected from the field (such as photographs, documents, and screenshots that laypeople can interpret). The broader categories from the later stages of coding can become the structure of chapters. “Scholarly literature, accessed later in the focused investigation and theoretical generation stages, becomes the basis for a literature review that explains any social, historical, economic, educational, and political issues that can contextualize the theory” (p. 56).

In critical GT, as with other contemporary forms of GT, it is not possible to be neutral. The question is whether critical GT betrays the origins of GT, as critical GT researchers may start to look as if they “manipulate data in order to influence policymakers and to shape public opinion… forcing the data into preconceived notions or categories” (p. 56). Hadley gives a few arguments against this accusation. First, critical GT emphasizes constant comparison, which means not only providing a single token opposing view, but constantly comparing the typical and outlying data. Second, similar to the critical education scholar Paolo Freire in Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Hadley states:

By viewing the area of study from the perspective of both the powerful and powerless, it is possible to see how ‘exploiter’ and ‘exploited’ may share certain similarities. Social processes of ‘victims’ [i.e., what the victims do] may be oppressive to others, and such issues cannot be ignored if they emerge during data collection. Critical grounded theorists should be allowed to give a voice to the voiceless, but only in a manner that is reflexively critical both of themselves and of their informants. (p. 57)

For critical grounded theorists concerned with a particular societal problem—as Hadley is concerned with the neoliberalization of EAP—he offers “the following caveat: If the perspective fits, use it. Otherwise, keep looking. Other problems and processes are equally as pressing, and a grounded theorist should try to be as open to as many different perspectives as possible” (pp. 57–58).

Summary: What unifies all the forms of GT, and how is GT different from other qualitative methodologies?

It should be clear by now that the same methods (e.g., interviews) can be part of wildly different methodological approaches, epistemologically speaking. The way Glaser would approach interviews is not how Clarke would approach them, and interviews in GT are not done for the same purposes and analyzed as they might be in action research (which is its own family of methods with different approaches).

However, Hadley offers the following characteristics of GT to show that this family of methods has a common gene pool: (1) start with open and later go to more focused sampling and coding (theoretical sampling/coding as the theory emerges), (2) constant comparison of memos that represent patterns and outliers, and (3) generating theory from the “ground up” with downplayed reliance on pre-existing theories. All these are central tenets of the method even as it evolved according to trends in qualitative research such as the “constructivist turn” of the 1980s and 1990s (which moved qualitative research away from positivism, and no longer sought objectivism) and the “critical turn” of the early 21st century, in which qualitative researchers became interested in social justice issues.

On the other hand, Hadley notes that GT is open to ALL three paradigms discussed earlier in this post, and with critical GT is moving back to paradigms of structure—trying to objectively see where the injustices lie, but through a process of social negotiation and individual reflexivity.

This ensures that “theorization takes place from not only those people and groups who, so to speak, have the power to keep the light on their own narratives but also among those who have been relegated to obscurity. Coding is omnivorous in choice [i.e., code anything, not just your research focus], rigorous in practice [i.e., do not cherrypick or pre-impose a worldview], but not onerous in the sense of stifling theoretical thinking” (pp. 60–61; my italics). The theory generated, because it is both methodologically rigorous and critical in orientation, can then be trustworthy enough to offer “humane solutions to social problems” and “new ways of pragmatic action” (p. 61).

Regarding how GT is different from other qualitative methodologies like ethnography, action research, case studies, and phenomenology, it is clear that there are methodological overlaps. Similar types of qualitative data are collected, mainly interviews and participant observation. Coding schemes are roughly the same—with the important point in GT that you never have any deductive (predetermined) codes. All codes in GT are inductive (coming from the “ground up”) or what Hadley calls “abductive” in these chapters on the history of GT (this is a new word for me… apparently it is a middle ground between deductive and inductive coding, but if 100% inductive coding is an impossibility given the researcher’s prior experience and worldview, maybe anything is really abductive coding if it is not deductive coding?).

Hadley posits that GT is different from case studies in that case studies involve existing theory (e.g., deductive codes). GT is different from action research in that action research is designed to solve problems, but GT only lays out the situation so that it can be better grasped and solutions/courses of action can be proposed. Practically, it sits between action research and phenomenology, which “describes the essence, meaning and experiences of those involved in a social phenomenon” (p. 62). In other words, GT is “pragmatic theorization about a substantive area of study” (p. 62). GT does not offer the same degree of “thick description” as ethnography with regard to the research site, but GT does require that adequate time is spent at the site to get to know the participants. In contrast, GT calls for “thick theorization” (p. 37), as stated in the previous chapter (Chapter 2), because so much is demanded of the researcher to construct the theory from the ground up, and more so than ethnography, GT seeks to generalize to similar contexts with the same issues or concerns.

Other qualitative researchers have copied the simultaneous process of data collection and analysis as GT researchers, and hence present findings and analysis together, unlike in quantitative research, but GT is very explicit in how codes are created from the data—“the first among qualitative research traditions to make such practices clear” (Richards, as cited in Hadley, 2017, p. 63). This is because GT seeks to be practical, to generate theories that can be acted upon, can be generalized to an extent, and are durable, “a helpful contribution to the working lives of teachers and, more broadly, to those outside our field as well” (p. 63). In other words, Glaser and Strauss and those who followed in their footsteps call for a socially accountable way of doing qualitative research, one that doesn’t just describe various themes but studies the words and actions of people in meticulous detail to create theoretical explanations (beyond the obvious) of the why’s and how’s of social processes. It is not mere description but theorization: “grounded theories are developed from a study of what actually took place… rather than that of validating the ideas of a famous scholar writing from somewhere far, far away” (p. 64).

In the next section of the book, Hadley addresses how to do grounded theory—shifting from “informed thought to pragmatic action” (p. 64). Stay tuned for part 2 of this blog post summarizing his informative and student-friendly handbook on grounded theory!

References

Benoliel, J. Q. (1996). Grounded theory and nursing knowledge. Qualitative Health Research, 6(3), 406–428. https://doi.org/10.1177/104973239600600308

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Sage.

Clarke, A. E. (Ed.). (2005). Situational analysis: Grounded theory after the postmodern turn. Sage.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1965). Awareness of dying. Routledge.

Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (1999/2017). Discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Routledge.

Hadley, G. (2015). English for academic purposes in neoliberal universities: A critical grounded theory. Springer.

Schatzman, L. (1991). Dimensional analysis: Notes on an alternative approach to the grounding of theory in qualitative research. In D. Maines (Ed.), Social organization and social process: Essays in honor of Anselm Strauss (pp. 303–314). Aldine de Gruyter.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research techniques. Sage.

Titscher, S., Wodak, R., & Meyer, M. (2000). Methods of text and discourse analysis: In search of meaning. Sage.

2 thoughts on “Grounded Theory in Applied Linguistics Research: A Practical Guide (part 1 of 2)”

Comments are closed.